Signer #100, Azaliah Schooley: "The Undocumented Immigrant"

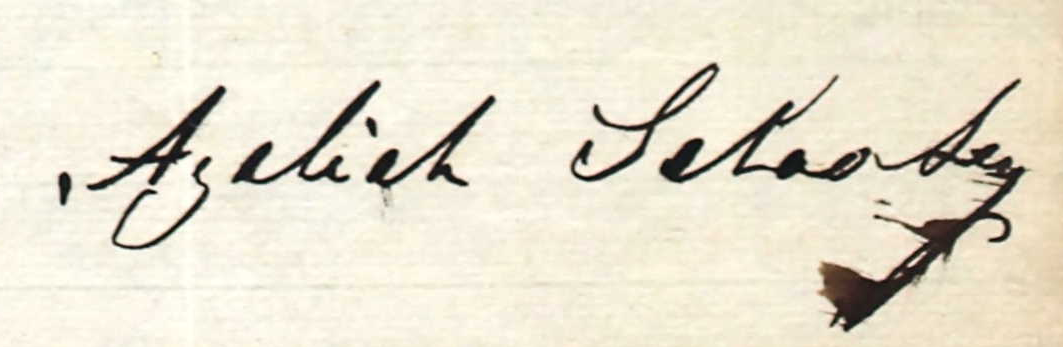

Signer #100, Azaliah Schooley

(b. Lincoln County, Ontario, Canada, circa 1805--d. Waterloo, New York, October 24, 1855)

The signatories section of the Declaration is divided into two parts, those being the signers who are women and, after that, the signers who are men. I would argue that significance can be derived from the order in which names are listed. If the vanguard of the proto-Suffragist leadership – names like Stanton's, Lucretia Mott's, Martha C. Wright's, and Jane Hunt's – are the first names included, it stands to reason that the larger sequence gives some indication of a quasi-organizational structure to the gathering.

When keeping this significance-of-sequence in mind, one's eye is drawn to Azaliah Schooley. The 100th and final signer, his name is the last one entered into the men's section of the Declaration. In something of a contrast, Azaliah Schooley's spouse, Margaret Schooley (Signer #7), is at the front of the line. Ordinally, Margaret Schooley is the seventh signatory of the Declaration. Her name is even listed before major figures like Wright, Hunt, and Amy Post. The contrasting orders in which the Schooleys (Margaret, seventh, and Azaliah, one hundredth) present an interesting juxtaposition.

At the time of the convention at Seneca Falls, the Schooleys resided in the outskirts of the nearby village of Waterloo, just a few miles due west of Seneca Falls. But Waterloo was only Azaliah Schooley's adopted hometown. He had only been naturalized as an American citizen as recently as the 1830s. In an "alien deposition" given on May 12th, 1837 and recorded in a New York State logbook of naturalized "resident aliens," Schooley admits to having illegally crossed the border. Schooley offers some of his backstory in the statement. He acknowledges that he was born in Lincoln County in the province of Upper Canada [Lincoln County is now in Ontario]. He discloses that he "arrived at Black Rock [now a suburb of Buffalo] in the State of New York about the first of May A.D. 1829, being about 24 years old," and that he had spent the interim residing in Waterloo. For good measure, he also swears in the document to “abjure and renounce all allegiance to said King of Great Britain and to all other princes and potentates whatsoever.” Schooley is assessed a fee of one dollar.

If Schooley immigrated to Waterloo by chance or choice, he could not have found himself in a more intense hotbed of radical Abolitionist-cum-feminist-cum-Quaker thought. Schooley himself would become a member of the Junius Monthly Meeting of Quakers in Waterloo. It is from this meeting house that the 1836 "Junius Proposal" would attempt to codify gender equality and women's equal practice more broadly throughout Quakerdom.[i]

And Schooley seems to have been a sort of social connector, introducing free thinking fellow travelers in the region. Preserved in the Post Family Papers at the University of Rochester, a June 1852 letter from Schooley, addressed to Isaac Post, provides a letter of introduction on behalf of one John C. Moore. Moore, Schooley reports to Post, has just relocated to Rochester and now resides "within the limits of Your City." Furthermore, Schooley hopes Post might engage Moore on "the investigation of those subjects pertaining to spiritual Philosophy." While also a noted Abolitionist Quaker, Post was at the forefront of the spiritualist movement. His volume of spirit writing, Voices from the Spirit World, in which Post relays the messages of historical figures from the great beyond, was published the same year. The bonds between Azaliah Schooley and Isaac Post might have been shared by their spouses. While Isaac Post is not one of the 100 signers of the Declaration, his spouse, Amy Post, is ordinally the 11th signer, only three spaces removed from Margaret Schooley.

In terms of gauging Azaliah Schooley's sympathies toward the cause of Abolition, he is repeatedly listed on the subscribers list of The Anti-Slavery Standard in the mid-1840s. Following Schooley's death as a result of consumption on October 24, 1855, The Liberator printed a heartfelt obituary. It remembers Schooley as being "firm to the true and right, his kind and gentle spirit subdued and conciliated their opposites, and won, almost universally, love and esteem. His philanthropy, as his religion, refused the limitations of sect or class."

Abolitionism, check. Spiritualism, check. Politically minded Hicksite, check.

Schooley's sympathies and activism extended not to any one of the schools of radicalism present at Seneca Falls. Schooley was involved in all of them.

At the time that he became a citizen of the United States, Azaliah and his family had recently weathered tragedy. Azaliah's first wife, Mercy Lundy Schooley, died on January 30, 1836, at the age of 27. She was survived by Azaliah and two children, Samuel and Levi. Azaliah's married Margaret Prall Shotwell, a native of Woodbridge, New Jersey, in 1838.[ii] The 1850 New York census includes the names of two more children living in the household, named Isaac and Margaret, the children of Margaret and Azaliah. A seventeen-year-old woman, Josephine, is Margaret's daughter.

Schooley is interred at the Quaker cemetery in Waterloo. Signer Rhoda Palmer is also buried there.

[Headstones of Azaliah Schooley (foreground) & Mercy Lundy Schooley (left, far background). Photo by author.]

[i] See Wellman 105.

[ii] See Armstrong 315.

Works Cited

"Abolitionists, Pay Your Debts!" The Anti-Slavery Standard, 1 February 1844, p. 139. Print.

"Alien Depositions of Intent to Become U.S. Citizens, New York, 1825-1871.” AncestryLibrary.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 June 2017.

Armstrong, William C. The Lundy Family and Their Descendants of Whatsoever Surname: With a Biographical Sketch of Benjamin Lundy. J. Heidingsfeld, 1902. Print.

"Azaliah Schooley" 1850 United States Federal Census. AncestryLibrary.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 June 2017.

"Died - Azaliah Schooley." Obituary. Cayuga Chief [Auburn, NY], 13 November 1855, p. 3. Print.

"Obituary - Azaliah Schooley." The Liberator, 23 November 1855, p. 187. Print.

Post, Isaac. Voices from the Spirit World: Being Communications from Many Spirits. Charles H. McDonnell, 1852. Print.

Schooley, Azaliah. "Letter to Isaac Post." Post Family Papers Project, University of Rochester. rbsc.library.rochester.edu/items/show/3850. Web. June 16, 2017

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010. Print.