Signer #13, Lydia Mount, "The Widow"

Signer #13: Lydia A. Hunt Mount

Born: 1802, New York City

Died: December 23, 1868, Waterloo, Seneca County, Age 65

Local Residence: 100 William Street, Waterloo

Special thanks to Lorie Dalola for research assistance provided in the production of this profile.

At the 1867 New York Constitutional Convention, author and reformer George William Curtis spoke in favor of a proposed motion to strike the word “male” from sections of the state constitution pertaining to franchise. The measure would have effectively given women the right to vote. A centerpiece of Curtis' argument involved the utter lack of professional opportunities afforded women. “And here are thousands of miserable women pricking back death and dishonor with a little needle,” he complains, “and now the sly hand of science is stealing that little needle away” (196-7).

Curtis’ allusion to “a little needle” would not have been lost on a contemporary audience. It refers, of course, to the sewing needle, the almost singular means of subsistence for countless American women. Needlework, in 1848 and thereafter, existed as one of the very few occupations that women could pursue in order to eke out a livelihood. And it does not take a degree in economics to realize that, if so many women were compelled to take up sewing as an only option, their vast labor pool would depress wages to the point that any income it yielded would remain agonizingly low. The alternative, the “death” kept at bay by the needle, is indigence and starvation. The “dishonor” Curtis speaks of is prostitution. Making matters worse, technological advances in the textile industry then threatened to decimate this sector of the economy entirely.

The vocational barriers imposed on women—and the economic hardships it instantly created—can be discerned in the life of Signer #13, Lydia Mount. Mount was poised to become the matriarch of one of Waterloo’s prospering, well-to-do local dynasties. The death of her husband in 1842 changed all this, effecting the gradual erosion of her wealth in the years that followed. The restrictions that blocked women’s participation in the sphere of business turned the death of a male breadwinner into a potential disaster of incalculable proportions. Not coincidentally, Lydia Mount spent the last day of her life laboring to support herself and her family. In contrast to Harriet Cady Eaton (Signer #2), whose fortune mysteriously grew after the death of her husband, the life of Lydia Mount is proof that a mounting frustration at systemic economic inequality was present at the Seneca Falls Convention.

Records indicate that Lydia A. Hunt was born in New York City some time around the year 1802. A genealogy, The Descendants of Thomas Hunt, reproduced on Rootsweb.com, identifies Lydia as the daughter of Richard Hunt and Mary Pell. Of Lydia’s five siblings, future signers of the Declaration include elder sister Hannah Hunt Plant (#26) and elder brother Richard P. Hunt (#69).

In Waterloo on October 30, 1824, Lydia married Randolph Mount, a native of New Jersey born in 1794. News of the nuptial was carried by The Geneva Gazette.

A notice also appeared in The Telescope of New York City.

According to Judith Wellman, Randolph and Lydia Mount, once settled in the area, affiliated with the Junius Monthly Meeting of Quakers (“Lydia Mount”). During this period, Randolph appears to have worked as a merchant in Geneva. A March 1827 advertisement appearing in The Geneva Gazette indicates that Randolph had been operating his business out of a building on Geneva’s Main Street.

In February 1827, the couple lost a daughter, Matilda or Caroline Matilda, a one-year-old. News of her passing was carried in The Geneva Gazette.

Subsequent census records reveal that Lydia and Randolph had a second daughter, Mary Elenor, the future Mary E. Vail (#56), in October 1827. Another daughter, Emeline, was born in December 1829, and a fourth, Eliza Jane or “E.J.,” arrived in November 1832.

Subsequent census records reveal that Lydia and Randolph had a second daughter, Mary Elenor, the future Mary E. Vail (#56), in October 1827. Another daughter, Emeline, was born in December 1829, and a fourth, Eliza Jane or “E.J.,” arrived in November 1832.

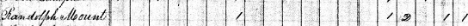

At some point in the late 1820s, the Mount family relocated to a 300-acre farm in the vicinity of Seneca Falls. The 1830 census for Seneca Falls designates Randolph as head of household. He resides with two other males and three females, two of whom are under age 5. By the 1840 census, Randolph resides as the sole male in a household with one female under age 10, two females under age 15, one female in her 20s, and one female in her 30s, likely Lydia.

Spouse Randolph Mount died suddenly on April 2, 1842, at age 49. Judith Wellman cites the possible cause as tuberculosis (“Lydia Mount”). He was interred at Maple Grove Cemetery in Waterloo (“Randolph Mount”). A probate letter identifies Lydia as executrix of her spouse’s estate, alongside co-executors brother Richard P. Hunt and an Elijah Quinby. One Daniel Kendig has been appointed as “special guardian” of the teenage children, Mary Elenor, Eliza Jane, and Emeline. George Pryor (#93) is given the role of appraiser, responsible for valuations of Randolph’s personal property. Judith Wellman notes that, following Randolph’s death, Richard Hunt helped to finance the schooling of Emeline and Eliza Jane in Ithaca (“Lydia Mount").

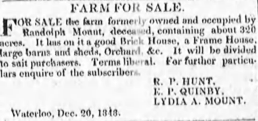

By the time of the Seneca Falls Convention, Lydia would have been approximately 46. She can be counted among the handful of widows who lent their signatures to the Declaration. This includes the best candidates for Phebe King (#35) and Betsy Tewksbury (#47). The next December, Lydia and the two other executors of her husband’s estate felt compelled to put the Mount family farm up for sale. A record from The Waterloo Observer, uncovered by Lorie Dalola, advertises “a Good Brick House, a Frame House, large barns and sheds, Orchard, &c.”

The notice contains a sense of financial urgency. The expression “Terms liberal” suggests that the executors are willing to be flexible regarding the transaction, perhaps hoping that generous terms might help to speed up the sale. Six years after Randolph’s death and only six months after the Seneca Falls Convention, it appears that looming financial pressures forced Lydia Mount and her family to abandon the property.

Lydia and her children thereafter relocated to the center of Waterloo. An 1852 village map situates the “Mount House” on William Street. With a transcription error mistaking the “L” of her given name for a “C,” Lydia Mount's address is listed in Brigham’s 1862 directory for Seneca County at 100 William Street (37).

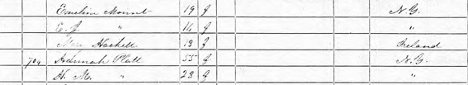

Lydia, 48, appears as head of household in the 1850 census for Waterloo. She lives with Emeline, 19; E.J., 15; and an Ireland-born teenager most likely hired on as a domestic. Identified as a separate family unit living under the same roof is sister Hannah Plant (errantly recorded as “Platt”) and a daughter “H.M.,” 23. The value of Lydia’s estate is $13,800.

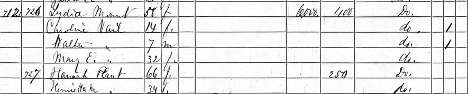

By the 1860 Waterloo census, Lydia’s wealth is assessed at $6,400. This amounts to less than half of its assessment a decade prior.

The household now contains three signers of the Declaration: Lydia, her daughter Mary E. Vail, and her sister Hannah Plant, whose estate is assessed at $250. Mary’s children, Caroline and Walter, also occupy the house alongside Hannah’s adult daughter, Henrietta.

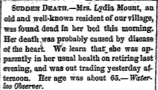

Lydia Mount died unexpectedly in her sleep on the night of December 23, 1868. She was about 65 years old. Her brief obituary in The Geneva Gazette attributes the passing of the “well-known resident of our village” to heart disease.

It also notes that she was “out trading yesterday afternoon,” which I take to mean that she was busy conducting some form of business on the day of her death. Another, more-substantial obituary in The Waterloo Observer remarks, poetically, that her death, “though mysterious and lamented,” was “scarcely less beautiful than her life. She only fell asleep. The hour is not known. There was no sound of the footfall of the messenger who came to take her. No family sympathy or tears were elicited by the dying strife, nor were human ministerings needed.”

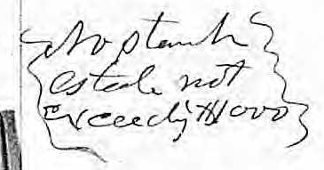

Signer #13 died intestate. A note scrawled in the bottom-lefthand margin of her January 1869 probate letter explains, “estate not exceeding $1000.” What remained of Lydia Mount’s wealth, it seems, would not merit a good deal of legal consideration, nor was it likely to be the subject of dispute among her inheritors. Lydia is buried next to spouse Randolph at Maple Grove Cemetery in Waterloo.

Lydia’s daughter Emeline married Benjamin Bacon, a farmer, in June 1852. Tending a tract of 100 acres, the couple had six children: Jennie, Anna, Emma, Clara, Mary, and Joel. Emeline died on February 25, 1888, at age 58 (Portrait 354).

Daughter Eliza Jane married Septimus Swift in January 1856. They had two children, Moses and Randolph. The couple lived briefly in New York City, where Septimus worked as a hat salesman. The couple resides in Waterloo in the 1880 census. Eliza Jane last appears residing with son Moses on Main Street in Waterloo in the 1900 census.

Women who outlived their husbands could expect to struggle under dire economic conditions. Her husband’s death clearly foisted a severe financial burden on Lydia Mount. The lack of professional avenues open to women—with the painful, lone exception of needlework—allowed Lydia Mount to hold onto to her family’s farm for only six years after Randolph Mount’s death. The dispossessions put into motion by his loss likely contributed to Lydia’s need to labor on the day that she died. The financial frustrations felt by local widows clearly added signatures to Declaration of Sentiments.

Works Cited

"Bacon Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

"Bacon Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. Self-published, 1862.

“Buildings to Let.” The Geneva Gazette, 28 Mar. 1827, p. 3.

Curtis, George William. Orations and Addresses of George William Curtis. Harper, 1894.

“The Descendants of Thomas Hunt.” Rootsweb.com, Accessed 20 July 2023. https://homepages.rootsweb.com/~huntpage/thomashunt0001.htm

“Died.” The Geneva Gazette, 28 Feb. 1827, p. 3.

“Emiline Mount Bacon.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 6 June 2023. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/40782709/emiline-bacon

“Farm for Sale.” The Waterloo Observer. 20 Dec. 1848. Fultonhistory.com, Accessed 24 July 2023.

“Lydia Mount.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 6 June 2023. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/40782499/lydia-mount

“Lydia Mount—Probate Letter.” Waterloo, New York, 1868. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999. Ancestry.com. Accessed 22 June 2023.

“Married.” The Geneva Gazette, 1 Nov. 1824, p. 3. “Married.” The Telescope, 20 Nov. 1824, p. 100.

"Mount Household.” Federal Census, 1830. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

"Mount Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

“Mount Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

“Mount Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

“Mrs. Lydia Mount.” The Waterloo Observer. 24 Dec. 1868. Fultonhistory.com, Accessed 6 June 2023.

Portrait and Biographical Record of Seneca and Schuyler Counties, New York. Chapman, 1895.

“Randolph Mount—Probate Letter.” Waterloo, New York, 1842. New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999. Ancestry.com. Accessed 22 June 2032.

“Randolph Mount.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/40782440/randolph-mount

“Sudden Death.” Geneva Daily Gazette, 25 Dec. 1868, p. 3.

"Swift Household.” Federal Census, 1880. New York, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

"Swift Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

"Swift Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 June. 2023.

“Waterloo Town and Village - 1850.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. Accessed 6 June 2023. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/.

Wellman, Judith. “Lydia Mount.”Women's Rights National Historic Park, NPS.Gov, Accessed 6 June 2023. https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/lydia-mount.htm