Signer #2: Harriet Cady Eaton, "The Rich Sister"

Signer #2: Harriet Eliza Cady Eaton

Born: October 5, 1810, Johnstown, Montgomery County

Died: March 11, 1894, Baltimore, Maryland, Age 84

Occupations: “HouseKeeper,” philanthropist

On the opening morning of the Seneca Falls Convention, the crowd gathered outside of the Wesleyan Chapel found themselves in a bit of a bind. They had been locked out of the building (perhaps by accident, perhaps not). An eleven-year-old named Daniel Cady Eaton, however, surmounted this obstacle and saved the day. Charlotte Woodward Peirce, Signer #37, later recalled, "it was a young man, whose name I don't remember, but who, I know, afterward became a professor at Yale, who volunteered to break in the door--perhaps it was a window, but anyhow he broke in, and we all followed him into the church" (Dorr 23). The most likely scenario involves young Daniel Eaton being hoisted up and wriggling through an open window before unlocking the front door from inside.

Had the boy and his mother, Harriet Eliza Eaton, not been in attendance that morning, the events of the day might have unfolded very differently. Harriet Eaton would go on to become the second signer of the Declaration of Sentiments; her signature is preceded only by that of Lucretia Mott. Signer #2 lived a less public life than her younger sister, Elizabeth Cady Stanton (#4), and she shied away from the political fray of the Suffrage Movement. But, by virtue of her being Stanton's sister, Harriet Eaton managed to provide invaluable support to the movement at a number of key inflection points.

The richest signer by far, Harriet Eaton was the modern-day equivalent of a multimillionaire. She had amassed a fortune by middle age, and the origin of this wealth is not entirely clear. Just how much of it was funneled toward her sister's political activities is an important, unanswered question.

Harriet Eliza Cady was born on October 5, 1810, in Johnstown, Montgomery County (later incorporated into Fulton County). She was the fifth of Judge Daniel Cady’s and Margaret Livingston’s ten children. Oddly, the Cadys' firstborn was also named Harriet or Harriot, and the two sisters' lives might have overlapped for a short time. A 1910 Cady family genealogy by Orrin Peer Allen contends the elder Harriet died in November 1810, in the month after the younger Harriet's birth (173-4). Signer #2's namesake and niece, Harriot Stanton Blatch (born Harriet Eaton Stanton) contradicts this, claiming that the younger Harriet was given the name at birth, after the death of her older sister (22).

The Cady family lived in a “fine brick residence” constructed in Johnstown. At the time of Signer #2’s birth, father Daniel Cady, a jurist and politician, was serving as a representative in the New York State Assembly (Allen 173-4). Because of alleged health problems, Harriet did not enjoy any formal education and did not attend the Troy Female Seminary like her younger sisters, Elizabeth and Margaret (Fairbanks 148-9). As Blatch later reports, Harriet "had been so delicate as a child that she had never had systematic schooling" (10).

On December 27, 1830, Signer #2 married a cousin, Daniel Cady Eaton. Daniel was seven years Harriet's senior and hailed originally from Catskill, Greene County (Allen 174). A marriage announcement published in The New York Evening Post describes the groom as a “merchant, of the firm of Doughty, Robertson and Co. of NYC,” located on Pearl Street (Bowman 80). This suggests that Daniel Eaton had already established himself in New York’s merchant class by the time he and Harriet were married. The couple had a daughter named Harriet on August 4, 1835, and a son named Daniel on June 16, 1837. Both children were delivered back in Johnstown (Allen 174-5).

In her autobiography 80 Years and More, Elizabeth Cady Stanton recalls visiting her sister and brother-in-law in New York City. The newlywed Stantons, bound for Europe and the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention, rendezvoused with the Eatons before setting sail. Stanton portrays Daniel Eaton in an endearing light: “He and I had had for years a standing game of ‘tag’ at all our partings, and he had vowed to send me ‘tagged’ to Europe. I was equally determined that he should not. Accordingly, I had a desperate chase after him all over the vessel, but in vain. He had the last ‘tag’ and escaped. As I was compelled, under the circumstances, to conduct the pursuit with some degree of decorum, and he had the advantage of height, long limbs, and freedom from skirts, I really stood no chance whatever. However, as the chase kept us all laughing, it helped to soften the bitterness of parting” (72-3).

The Eatons were well-off enough during this period to make their own trips abroad. This is revealed in Stanton's description of how Harriet helped with her sister's transition from Boston to Seneca Falls in 1847. Stanton remembers that in Boston, “Mr. and Mrs. Eaton and their two children arrived from Europe, and we decided to go together to Johnstown, Mr. Eaton being obliged to hurry to New York on business, and Mr. Stanton to remain still in Boston a few months. At the last moment my nurse decided she could not leave her friends and go so far away. Accordingly my sister and I started, by rail, with five children and seventeen trunks, for Albany, where we rested over night and part of the next day. We had a very fatiguing journey, looking after so many trunks and children, for my sister's children persisted in standing on the platform at every opportunity, and the younger ones would follow their example. This kept us constantly on the watch” (143). I take this to mean that, at every rail station, the Stanton and Eaton cousins would leave the train to explore the busy platform area--a frightening prospect for any parent. On the way west, the sisters stopped in Johnstown to visit their parents, unannounced and in the middle of the night.

Harriet happened to be visiting Elizabeth in July of the following year, which happened to coincide with the Seneca Falls Convention. The circumstances surrounding Harriet’s presence in the village as an out-of-towner are strikingly similar to those of Lucretia Mott. Like Harriet, Mott was in the area, paying a summer visit to her sister Martha Coffin Wright (#8), who lived in nearby Auburn. Both Mott and Eaton were upwards of 260 miles from their residences in Philadelphia and New York City, respectively. Consequently, Eaton and Mott are in a virtual tie as the signers who had traveled farthest from their homes for the Seneca Falls Convention.

Despite the obvious prominence of being the second signer, Harriet Eaton allegedly came to regret lending her name to the Declaration of Sentiments. According to convention lore, she later requested that her signature be removed from the document. She apparently came to feel the brunt of the public stigma that her association with the convention's radical politics had attracted. Judge Daniel Cady even traveled to Seneca Falls to check on his daughters’ abnormal behavior in the aftermath (Cullen-Dupont 60).

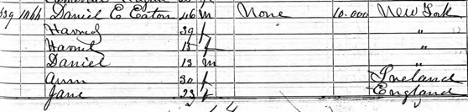

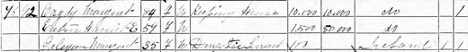

The Eatons appear in the 1850 census in “the Western Half 15 Ward” of New York City. Daniel is 46, and Harriet is 39. Under the same roof are their two teenage children, Harriet, 15, and Daniel, 13, as well as two foreign-born domestics. A dry goods retailer by trade, Daniel’s occupation is listed oddly as “None,” and the family’s wealth is assessed at a respectable $10,000.

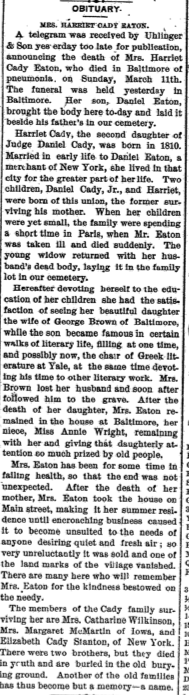

Shattering their upper-middle-class tranquility, the Eaton family experienced tragedy in the 1850s. On a family trip to Europe, Daniel Cady Eaton (Sr.) died unexpectedly in Paris (Allen 174). The incident would be later described: “When [Harriet's] children were yet small, the family were spending a short time in Paris, when Mr. Eaton was taken ill and died suddenly. The young widow returned with her husband’s dead body" (“Obituary”).

A July 1855 passenger manifest for the steamship Arago, returning to New York from its maiden voyage to Liverpool and Havre, bears the names of the surviving Eaton family (“Launch”). Daniel Eaton's remains were most likely transported in the cargo hold of the Arago on the sad return home. He is interred in the Cady family plot in Johnstown (“Daniel Eaton”).

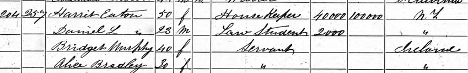

After Daniel's passing, something mysterious happened. The 1860 census for New York City captures Harriet, now a widowed, 50-year-old “HouseKeeper,” living with son Daniel, 23, who is a student at Columbia Law. They live with two Irish-born domestics.

Harriet’s wealth is here valued at $40,000 in real estate and $100,000 in personal property. This represents a staggering increase from the Eatons’ 1850 worth of $10,000. According to an online inflation calculator, Harriet’s net worth of $140,000 would equal more than $4.5 million dollars in today's money. As one point of comparison, Henry Seymour (#75), who built a Seneca Falls business empire in pump-making and yeast cakes, is assessed to be worth $37,000 in the same census. Harriet Eaton is, by far, the richest signer profiled. Simply maintaining a fortune of this size must have required a good deal of financial acumen on Harriet's part.

It is unclear exactly where this money came from. What should be made of the explosion of Harriet’s wealth during this decade? It is possible that she received a life insurance payout upon the death of her husband. Or the money could have come from a relative's inheritance. The Eatons' proximity to Wall Street might have imparted some know-how and insight in playing the stock market. Another possible explanation is that the fortune proceeded from real estate speculation in New York City. In 80 Years and More, Stanton describes her sister's residence: “We found my sister Harriet in a new home in Clinton Place (Eighth Street), New York city, then considered so far up town that Mr. Eaton’s friends were continually asking him why he went so far away from the social center, though in a few months they followed him” (107). Purchasing land in advance of the city’s expansion might have produced a financial windfall for the Eatons.

Not one to be neglected as a potential major donor, Harriet lent her name to a petition introduced to Congress on behalf of universal franchise in 1866. This was the only instance I could find of Signer #2's direct involvement with the Suffrage Movement after 1848. Introduced by Thaddeus Stevens on January 29, the document was part of the scramble to win franchise for black men and all women during the postwar absence of conservative Southern legislators. In its preamble, the “Women of the United States” request “an amendment of the Constitution that shall prohibit the several States from disfranchising [sic] any of their citizens on the ground of sex.” It adds, “The experience of all ages, the Declarations of the Fathers, the Statute Laws of our own day, and the fearful revolution through which we have just passed, all prove the uncertain tenure of life, liberty and property so long as the ballot—the only weapon of self-protection—is not in the hand of every citizen.”

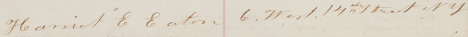

Harriet’s is the seventh signature on the petition, following those of her sister, Susan B. Anthony, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Lucy Stone, and others. Her address has been entered by hand as “6. West. 14th Street NY.”

During the 1860s, Harriot Stanton Blatch remembers summering in Johnstown with her grandmother and aunts. Aunt Harriet often escorted Harriot upstate from New York City on these trips. In 1870, Harriet, 59, resides in Johnstown her widowed mother, Margaret, 84. Harriet’s father, Judge Daniel Cady, had passed away in 1859 (Allen 173). Her mother’s worth is estimated at $20,000. Harriet, on the other hand, has real estate and personal assets valued at $51,500.

Mother Margaret Livingston passed away in September 1871, and Harriet apparently elected to remain in the family home in Johnstown (Allen 173). The 1875 New York census shows her residing there with two Irish domestics. Even though she would live for two more decades, this was the last census in which I could locate her.

Harriet continued to summer in Johnstown, otherwise freely touring the East Coast to call on relatives and friends (“Obituary”). During these years, she also drew from her wealth to fund the education of her nieces, including Harriot Stanton Blatch, as a means of compensating for her own lack of formal childhood education. Blatch remembers that she pursued her own early education out of a desire to please her aunt, and the two negotiated the terms of Blatch's education at the "dame school" of one schoolmarm, "Mother Yost," in Johnstown (Blatch 10-11). At the behest of “Aunt Had,” niece Harriot later attended Vassar College. She matriculated to Vassar despite her preference for Cornell, primarily out of Aunt Harriet’s disdain for coeducational institutions (“Harriot Blatch,” Dubois 19, Baker 120, Blatch 36). Blatch would become one of the leaders of the Suffrage Movement's second generation.

Harriet's son Daniel, the convention attendee, graduated from Yale in 1860, attended law school briefly, and served for a time in the Seventh Regiment of the New York Militia during the Civil War. In 1869, he was appointed professor of Art History and Criticism at Yale College. In this capacity, he published a number of books on European sculpture and painting, making several extended research trips to France and Germany during his lifetime. He married Alice Young in 1861, and they would have no children. He lived until 1912 and lies buried in New Haven (Philips 917, “Daniel Cady”).

In 1857, Harriet’s daughter Harriet married a Baltimore banker named George Stewart Brown (Allen 157). Elizabeth Cady Stanton is recorded traveling to Maryland for the birth of the couple’s first child, Alexander (Gordon 382). The Brown family appears to have been quite successful: by the 1880 census, they reside with six household servants. Brown's manifold business engagements are remembered by one source as including “President of the Baltimore and Havana Steamship Company, Director of the National Mechanics' Bank, a Manager of the House of Refuge, a member of the Boards of the Blind Asylum and of the Maryland Bible Society, Trustee of the Peabody Institute, Vice President of the Canton Company, Director in the old Calvert Sugar Refinery Company, and the Union Railroad Company” (“George Brown”).

Some time after 1875, Harriet elected to live permanently with her daughter in a residence on Cathedral Street in Baltimore. Son-in-law George Brown would pass away in 1890. The passing of Signer #2's daughter, Harriet Eaton Brown, is recorded in the January 28, 1893 edition of The Johnstown Daily Republican. It reports, “the many friends of the Cady family will regret to learn of the dangerous illness of Mrs. George Brown, daughter of Mrs. Daniel C. Eaton” (“Many Friends”). After her daughter's death, Harriet remained in Baltimore. She appears in an 1894 city directory, residing on 712 Cathedral Street (401).

Signer #2 died of pneumonia in Baltimore on March 11, 1894. An extended obituary was printed in The Johnstown Daily Republican (“Obituary”). Her body was transported by son Daniel Cady Eaton to Johnstown, where she is interred. “Another of the old families has thus become but a memory—a name,” her obituary remarks.

A second obituary was run in The Daily Morning Journal and Courier of New Haven, Connecticut, where son Daniel lived. It remembers her fondly: “All who knew her will recollect the mental rigor and brightness which distinguished her and rendered her aside from her charming presence a most entertaining companion and friend” ("Obituary").

In the coming months, The Daily Republican reports that “the Friends of the late Mrs. Harriet Cady Eaton will be glad to learn that with her customary thoughtfulness she has provided for those to whom in life she was so find a friend and mistress. Miss Mary Nickloy and Margaret Gallagher are among those thus remembered, the one with a monthly payment during life, the other with a small annuity” (“Friends”). Margaret Gallagher, one of the recipients of stipends bequeathed here by Harriet, appeared as a domestic in the 1870 census in Johnstown, working in the Cady household.

The Republican on April 17, 1894, notes that Harriot Stanton Blatch had arrived in New York from her home in England to address “a party of ladies, gathered in the interests of Equal Suffrage” in Johnstown (“Blatch”). In the very same column on the same day, a description of the growing Cady family plot in the town cemetery is given. A stoneworker was seen “carving the name of Harriet Eliza Eaton upon the monument erected long ago to the memory of her husband,” located “not far from the ponderous tomb selected to mark Judge Cady’s grave…Years ago it was the only piece of statuary in the cemetery and was very much admired” (“Sunny Days”). The proximity of the two articles capture the connection between generations of Cadys/Eatons/Stantons and the work that had been passed from one generation to another.

Some key questions remain about the life of Signer #2. What was the exact source of her wealth? Did any of that wealth go toward supporting the political endeavors of her sister? Again and again, Harriet Eaton indirectly assisted the Suffrage Movement in invaluable ways, serving often as a kind of silent partner. Did this same approach hold true in terms of her financial support for the Suffrage Movement? Without the understated involvement of Harriet Cady Eaton, historical events might have transpired in a very different way.

Works Cited

Allen, Orrin Peer. Descendants of Nicholas Cady of Watertown, Mass. 1645-1910. Self-published, 1910.

Baker, Jean H. Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists. Macmillan, 2006. Baltimore City Directory for 1894. R.L. Polk, 1894.

“Blatch.” The Johnstown Daily Republican. 17 Apr. 1894, p. 7.

Blatch, Harriot Stanton, and Alma Lutz. Challenging Years: The Memoirs of Harriot Stanton Blatch. Hyperion Press, 1976.

Bowman, Fred Q. 10,000 Vital Records of Eastern New York, 1777-1834. Genealogical Publishing Co., 1987.

Cullen-Dupont, Kathryn. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Women’s Liberty. Facts on File, 1992.

“Daniel Cady Eaton Household.” Federal Census, 1850. New York City, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Daniel Cady Eaton (Sr.).” Findagrave.com. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/115027822/daniel-cady-eaton.

“Daniel Cady Eaton Household.” Federal Census, 1880. New Haven, Connecticut. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Daniel Cady Eaton (Jr.).” Findagrave.com. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/147374342/daniel-cady-eaton.

Dorr, Rheta Childe. “The Eternal Question.” Colliers, The National Weekly, 30 Oct. 1920, pp. 5-6, 23-24.

DuBois, Ellen Carol. Harriot Stanton Blatch and the Winning of Woman Suffrage. Yale U P, 1999.

Fairbanks, Mary Mason. Emma Willard and Her Pupils: Or, Fifty Years of Troy Female Seminary, 1822-1872. R. Sage, 1898.

“The Friends of the Late Mrs. Harriet Cady Eaton.” The Johnstown Daily Republican, 7 May 1894, p. 7.

“George Brown Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Baltimore, Maryland. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“George Brown.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/55402774/george-stewart-brown.

Gordon, Ann D. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: In the School of Anti-Slavery, 1840 to 1866. Rutgers U P, 1997.

“Harriet Eaton Household.” Federal Census, 1860. New York, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Harriet Eaton Household.” New York State Census, 1875. Johnstown, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Harriet Eliza Cady Eaton.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/115027629/harriet-eliza-eaton.

“Harriot Stanton Blatch.” Vassar College Encyclopedia, https://www.vassar.edu/vcencyclopedia/alumni/harriott-stanton-blatch.html. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Launch of a Steamship.” The Daily Union (Washington, D.C.), 26 Jan. 1855, p. 3.

“Many Friends.” The Johnstown Daily Republican, 28 Jan. 1893, p. 3.

“Margaret Cady Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Johnstown, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Obituary—Mrs. Harriet Cady Eaton.” The Morning Journal and Courier (New Haven, Conn.), 12 Mar. 1894, p. 2.

“Obituary—Mrs. Harriet Cady Eaton.” The Johnstown Daily Republican, 15 Mar. 1894, p. 5.

“A Petition for Universal Suffrage—1866.” Center for Legislative Archives, https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/suffrage. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

Phillips, Andrew. “Daniel Cady Eaton: An Appreciation of His Life and His Influence Upon Art.” Yale Alumni Weekly, vol. 21, no. 37, 31 May 1912, p. 917-918.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Eighty Years and More. European Publishing Company, 1897.

“Steamer Arago-Passenger Manifest.” Port of New York, 1855. Ancestry.com, Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

“Sunny Days.” The Johnstown Daily Republican. 17 Apr. 1894, p. 7.