Signer #53, Susan R. Doty: “The Family Business”

Signer #53: Susan Russell White Doty

Born: August 15, 1807 or 1808, New Bedford, Massachusetts

Died: May 30, 1852, Macedon, Wayne County, Age 44 or 43

Occupations: Business Owner, Anti-Slavery Activist

Local Residence(s): Macedon, Wayne County

Susan R. Doty (Signer #53) and her spouse, Elias J. Doty (#78), were part of a contingent of Declaration signers hailing from the Quaker community in the village of Macedon, Wayne County. A historical marker sits today at the site of the Doty farm, and the 30-mile journey from that spot to Seneca Falls would have been a formidable one in 1848 (“Doty Home”). While the Dotys are remembered as Abolitionists and Suffragists, one aspect of Susan Doty's life that has gone unnoticed is her role as the scion of a lucrative family business, which oversaw the manufacture of a widely recognized commercial brand. A medicinal ointment concocted by Susan's father, Peleg White's Sticking Salve remained in production well into the 20th century, generating a customer base that was, by all appearances, very devoted.

More remarkably still, Susan Doty and her mother, Eunice White, assumed control of the family business after her father's passing in the late 1830s. The history of Peleg White's Salve, as a women-run enterprise, constitutes a rare exception to the professional and economic barriers that women faced in the 19th century. And Susan's later involvement with some of the key figures of the Spiritualism Movement complicated the company's inner-workings in unusual ways. It just so happens that Susan's father would play an active role in the family business long after his death.

According to Ethan Allen Doty’s The Doty-Doten Family in America (1897), Susan Russell White was born near New Bedford, Massachusetts, on August 15, 1807. She was the daughter of Peleg White and Eunice Tripp White (543). The White family migrated from Massachusetts to Ledyard, Cayuga County, in 1811. Part of a caravan of 32 Quakers, Susan and her parents came along with her siblings, Abner, Amy, and David (Howland 73, 88). During her childhood, Susan made the acquaintance of Amy Post (#10) and Isaac Post, who were her neighbors in Ledyard (Hewitt 50).

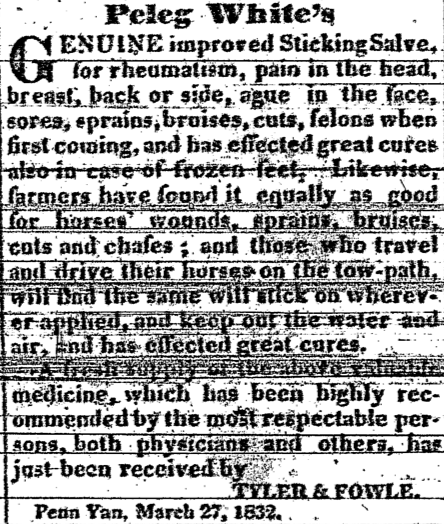

At some point around 1822, Peleg White first produced the miracle cure that would bear his name. But what was this concoction and how was it used? A 1966 article offers some background, explaining that Peleg White's “was compounded largely of pitch and beeswax" and "was sold in a stick like old-fashioned sealing wax. It was applied holding the stick over the area to be treated, applying a match, and letting the melted drops flow into the wound. This was far from a painless process.” Even by the second half of the 20th century, one might still encounter “an ardent champion of Peleg White who still has a limited supply on hand,” a diehard clinging to the last of their stash years after the product had been discontinued (“Miracle”). The salve was intended primarily as a remedy for wounds, but it might be useful on a variety of other ailments. An 1832 advertisement, one of hundreds run over the course of decades, touts Peleg White's for cases of "rheumatism, pain in the head, breast, back or side, ague in the face, sores, sprains, bruises, cuts, felons when first coming, and has effected great cures also in in case of frozen feet” (“White’s”). A “felon” in this instance is a bacterial infection of the fingertips. Beyond people, White’s salve could also be used to treat injuries on horses. Evidently, the burning hot liquid worked to some degree as an antiseptic, while the pitch and beeswax helped to close off the wound from further infection.

Susan married George Washington Doty in Scipio on May 28, 1829. George Doty was a farmer, and the couple had two daughters, Amie Anne, born in 1830, and Harriet Alice, born in 1831. For causes unknown, George Washington Doty died in Venice, New York, on December 15, 1831. Susan thereafter re-married on March 27, 1833, to George’s twin brother, Elias J. Doty (Doty 543). Marriage to a spouse's surviving sibling seems to have been a commonplace practice in the culture of the day. After the death of his wife, Stephen E. Woodworth, Signer #91, for example, married his brother's widow.

Susan married George Washington Doty in Scipio on May 28, 1829. George Doty was a farmer, and the couple had two daughters, Amie Anne, born in 1830, and Harriet Alice, born in 1831. For causes unknown, George Washington Doty died in Venice, New York, on December 15, 1831. Susan thereafter re-married on March 27, 1833, to George’s twin brother, Elias J. Doty (Doty 543). Marriage to a spouse's surviving sibling seems to have been a commonplace practice in the culture of the day. After the death of his wife, Stephen E. Woodworth, Signer #91, for example, married his brother's widow.

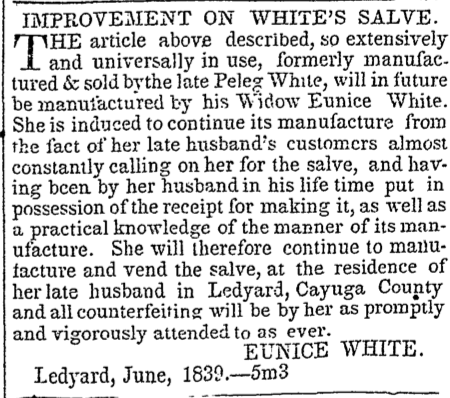

Susan's father died some time in the late 1830s. Facing the loss of her husband, Eunice White mounted a highly unusual response by personally assuming control of the family business. A brief notice of this transition, bearing a Ledyard dateline, appears briefly in The Auburn Journal and Advertiser in the summer of 1839. Following Peleg White's death, the manufacture of his eponymous mixture was to be taken up “by his Widow Eunice White.”

The new organizational structure of the business is announced unceremoniously and almost by way of apology. Eunice is in charge now, after being “induced to continue its manufacture from the fact of her late husband’s customers almost constantly calling on her for the salve, and having been by her husband in his life time put in possession of the receipt for making it, as well as a practical knowledge of the manner of its manufacture. She will therefore continue to manufacture and vend the salve, at the residence of her late husband in Ledyard, Cayuga County.” The notice also contains something of a stern warning to any fraudsters who might capitalize on Peleg’s death by hawking knockoff ointment: “All counterfeiting will be by her as promptly and vigorously attended to as ever.” Now was not the time to take advantage of a grieving widow.

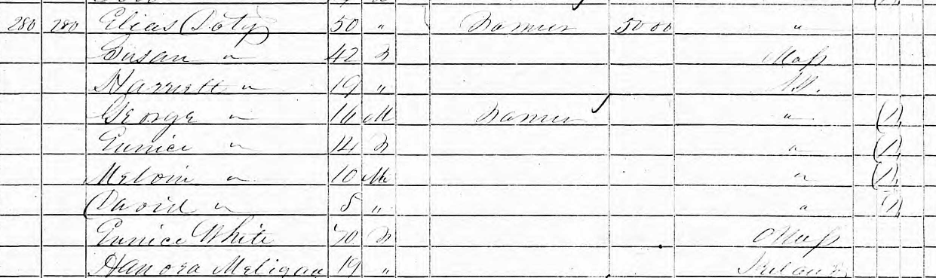

Between 1838 and 1845, Susan and Elias moved to Macedon. The couple had three children while still in Cayuga County: George Washington in 1834, Eunice White in 1836, and Milton White in 1838, all born in Venice. After the Dotys relocated to Macedon, they had a third son, David Raymond, in 1845 (Doty 543). The family appears in the 1850 census for Macedon.

Elias is a farmer with an estate valued at $5,000. Under the same roof, are Eunice White, now 70, and Hanora Meligan, 19, an Irish servant.

Now residing at the heart of the Burned-Over District, both Susan and Elias became heavily involved in the activisms then flourishing in the region. Susan was elected as an officer of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society (WNYASS) and she would work to organize grassroots fundraising events for the cause of Abolition (Hewitt 144, 156). An August 1849 letter penned by Susan, addressed to lifelong friend Amy Post, captures the whirlwind of activity. Digitized in the Post Family Papers Project, the letter updates Post, then living in Rochester, about Susan's efforts to stage an anti-slavery fair in Macedon. “I hasten to state to thee," she writes, "the prospect of our having a fair after making some investigation on the subject.” Working with signer Maria E. Wilbur (#61), Susan has started to scout locations in Macedon. One venue, “a very pleasant ballroom,” was maintained by an owner sympathetic to the cause, who would need “about two dollars” for the event. The venue had facilities for “boiling coffee” and Susan surmises, “I think it best to have lemonade & ice cream.” This idea has hit something of a roadblock because “Maria fears ice cream will be unhealthy.” From Post, Susan requests “a few newly made crackers, and candies,” which “could be obtained cheaper” in Rochester. Susan also adds that her spouse will be paying a visit: “Elias wishes me to say he will be at Rochester on sixth day morning.”

In another letter from the following November, Susan describes her frustrations with launching a local sewing circle. The group would, ideally, produce fabric goods that could be sold to support anti-slavery activism. An early meeting of the circle was “discouraging as we had only three (besides ourselves),” but a subsequent gathering had 13 quilters in attendance. Susan mentions that Maria Wilbur had set to work procuring materials and patterns for additional quilting.

Another letter from Susan Doty to Amy Post was sent some time in the early 1850s, but an exact year was omitted by the author. In it, Susan covers a variety of topics. She asks Post for advice about her daughter Eunice White Doty attending school in Rochester. Perhaps the Posts would board Eunice if she matriculated? Susan also brings up an unknown illness she is struggling with: “I had quite a severe attack of distress in my stomach last evening, similar to those in the first of my sickness, which has reduced my strength considerably but being free from pain today feel quite comforted.” Furthermore, “my cough has been worse since my return.”

Susan then turns to Post for help in the affairs of the family business. “Mother received her letter kindly but thinks she would like to know the particulars of how father would wish the property divided if Isaac should get any more communication from any of our friends please send them when thee writes should Isaac feel at liberty at any time to come out I hope thee will not stay away.” Both Susan and Elias, like the Posts, had become deeply invested in Spiritualism. Isaac Post, famously, acted as a medium, producing communications from the dead via automatic writing (allowing the hand to write freely as it was guided by spirits). Isaac Post’s Voices from the Spirit World, Being Communications from Many Spirits (1852) consists of posthumous letters from the great beyond, with contributions from the likes of Voltaire, Margaret Fuller, and Benjamin Franklin.

In the letter, Susan asks Amy to see if Isaac might reestablish contact with her deceased father, Peleg White. Hopefully, Peleg could dictate his wishes on how the assets of his estate should be allocated. Susan adds in a postscript, “please commit this to the flames when read,” a request that Post failed to honor. Perhaps Susan wanted the pages destroyed because they revealed a trade secret: her dead father was still paranormally involved in the executive decisions of the family business.

Susan broaches the same topic with Amy Post yet again in November 1851. She first describes, at length, the health of her daughters and her mother. The latter, she worries, may be nearing the end, and that prospect held distinct consequences for Peleg White's. “The subject to which I wish to allude is Mother’s business affairs, thee and I spoke of it before we left but I then thought as she seemed to be gaining it would do to wait for a few days or weeks but she has had and still has severe pains in one eye which is mostly nights, and I think it prevents her from a gaining strength, and produces some fever.” Elias Doty has gone to the doctor for help, thinking his mother-in-law's illness might be due to a tooth infection. Eunice White has temporarily recovered, to a degree, and “is now perfectly sensible and I think capable of giving directions in her business, and I do not know but something more may set it, which will deprive her again of such faculties.”

Susan broaches the same topic with Amy Post yet again in November 1851. She first describes, at length, the health of her daughters and her mother. The latter, she worries, may be nearing the end, and that prospect held distinct consequences for Peleg White's. “The subject to which I wish to allude is Mother’s business affairs, thee and I spoke of it before we left but I then thought as she seemed to be gaining it would do to wait for a few days or weeks but she has had and still has severe pains in one eye which is mostly nights, and I think it prevents her from a gaining strength, and produces some fever.” Elias Doty has gone to the doctor for help, thinking his mother-in-law's illness might be due to a tooth infection. Eunice White has temporarily recovered, to a degree, and “is now perfectly sensible and I think capable of giving directions in her business, and I do not know but something more may set it, which will deprive her again of such faculties.”

Susan asks Amy to come to Macedon in order to conduct a séance and dispense advice. She would gladly compensate Amy for the trouble. “Mother could see more the necessity of doing something soon, by renewing father’s communication, to her, or perhaps there might be something more from him, which would urge her to attend to it, besides I think she would receive such advise [sic] from you more kindly than from any others, and if then Isaac does not wish to draw the writing; we will get a lawyer from Palmyra to do it and you may witness it.” Susan clearly wanted her mother to make final proprietary arrangements in the event of her death. Some gentle prodding from Peleg White, with the help of the Posts' spiritual intercession, was bound to help.

The following spring, Susan R. Doty died on May 30, 1852, at age 43 or 44. She is interred at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester. She lived only four years after the Seneca Falls Convention, the shortest amount of time of any signer profiled so far (“Susan Doty”).

Of Susan's two biological children by her first husband, Amie Ann would marry a farmer named William Lapham. The Laphams resided in Macedon. Amie had two sons, George and Albert, and she died in 1859 (“Amie Ann Lapham”). Harriet would marry Jonathan Smith, a lumber merchant, and relocate to Chicago. She would have three daughters, Julia, Elizabeth, and Susan. She lived to 1924, passing at age 92 (“Harriet A. Smith”).

In spite of Susan’s concerns for her mother’s health in 1851, Eunice White would live to be 102. In 1860, Eunice appears in the Macedon home of her son-in-law Elias Doty. She would afterwards live with her daughter Eunice Smith in Farmington, Ontario County, where she appears in the 1870 census. The Cazenovia Republican would report on Eunice’s death in 1877, at Macedon, noting wryly that “there seems to be an unusual mortality among centenarians.”

Prior to her death, The Yates County Chronicle had run a more-staid account of Eunice’s life, identifying her as the widow of Peleg White. The piece fails to identify her as the woman who took control of the Peleg White brand at the time of her spouse's death.

In 1916, Peleg White’s Salve proudly celebrated the 94th year of its existence. It was still advertised in newspapers, paired with testimonials from satisfied customers. From Batavia’s Daily News:

Susan R. Doty’s involvement in the family business is a rarity, especially given the lack of professional avenues open to women at this moment in history. Her father’s death called upon her mother to take the reins of the company. Because of the family’s involvement with the Posts, the ghost of Peleg White would remain intimately involved in his family’s business dealings. Generally, spiritualism gave women power, via their perceived ability to channel the voices of the dead. The communications that did arrive from the hereafter just happened to be extremely feminist and egalitarian in nature, decrying slavery and calling for women's economic and legal emancipation. In the case of Peleg White’s Sticking Salve, consultations with the ghost of the inventor might have given a women-run business the veneer of masculine legitimacy and authority in a world where women were afforded virtually no professional opportunities.

Susan R. Doty’s involvement in the family business is a rarity, especially given the lack of professional avenues open to women at this moment in history. Her father’s death called upon her mother to take the reins of the company. Because of the family’s involvement with the Posts, the ghost of Peleg White would remain intimately involved in his family’s business dealings. Generally, spiritualism gave women power, via their perceived ability to channel the voices of the dead. The communications that did arrive from the hereafter just happened to be extremely feminist and egalitarian in nature, decrying slavery and calling for women's economic and legal emancipation. In the case of Peleg White’s Sticking Salve, consultations with the ghost of the inventor might have given a women-run business the veneer of masculine legitimacy and authority in a world where women were afforded virtually no professional opportunities.

Works Cited

“Amie Ann Lapham.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/65569821/amie-ann-lapham.

Doty, Ethan Allen. The Doty-Doten Family in America. Vol. 2. Brooklyn, New York: self-published, 1897.

“Doty Home Historic Marker.” Wayne County Historic Sites, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://www.waynehistorians.org/Places/site.php?site=871.

"Doty Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Macedon, Wayne County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

"Doty Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Macedon, Wayne County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

Doty, Susan R. “Letter to Amy Kirby Post, August 1849.” Post Family Papers Project, University of Rochester Library, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://rbscpexhibits.lib.rochester.edu/viewer/3039.

---. “Letter to Amy Kirby Post, November 1849.” Post Family Papers Project, University of Rochester Library, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://rbscpexhibits.lib.rochester.edu/viewer/3055.

---. “Letter to Amy Kirby Post, August 185-.” Post Family Papers Project, University of Rochester Library, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://rbscpexhibits.lib.rochester.edu/viewer/3068.

---. “Letter to Amy Kirby Post, November 1851.” Post Family Papers Project, University of Rochester, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://rbscpexhibits.lib.rochester.edu/viewer/3191.

“Harriet A. Doty Smith.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10288233/harriet_a-smith.

Hewitt, Nancy. Radical Friend: Amy Kirby Post and Her Activist Worlds. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Howland, Emily. “Historical Sketch of Friends in Cayuga County, N.Y., 1795 to 1828.” Collections of Cayuga County Historical Society, 1879, pp. 47-97.

“Improvement on White’s Salve.” Auburn Journal and Advertiser. 21 Aug. 1839, p. 4.

"Lapham Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Macedon, Wayne County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

McFarland, Paul. “Miracle Drugs in 1905.” The Brighton-Pittsford Post (Pittsford, New York), 18 Aug. 1966, p. 1.

“An Old Resident.” Yates County Chronicle, 18 Jun. 1874, p. 3.

“Peleg White’s.” The Penn-Yan Enquirer, 14 Nov. 1832, p. 4.

“’Peleg White’ Ninety-Four Years Old.” The Daily News (Batavia, New York), 15 Sept. 1916, p. 8.

“Personal.” Cazenovia Republican, 29 Mar. 1877, p. 1.

"Smith Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Farmington, Ontario County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

"Smith Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Chicago, Cook County, Illinois. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024.

“Susan R. Doty.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Dec. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8008441/susan_russell-doty.