Signer #54: Rebecca Race, "Mother of Twelve"

Signer #54: Rebecca M. Turner Race

Born: 1807, Maine

Died: July 17, 1895, Age 87-8

Occupation: “Keeping House”

Local Residences: Green Street, Seneca Falls; 25 Cayuga Street, Seneca Falls

Rebecca Race, Signer #54, gave birth to twelve children over the course of her lifetime. By the time of the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, six had perished. Only five of Race's children would outlive her, and four would survive to see the turn of the 20th century. William Peck’s 1908 History of Rochester and Monroe County memorializes this sad fact. Among the Race family, Peck remarks that there “were twelve children, but only three are living” (764).

The high death rate among Rebecca Race’s daughters and sons is indicative of a broader reality surrounding childhood mortality in the 19th century. In a survey of the 1850 census, researcher Richard Steckel found that, out of a random sample of 329 American children born that year, 23.4% percent were not present in the census of 1860 (334). Steckel allows for the possibility that many of these individuals could have been renamed, relocated, or miscounted in that interval. Otherwise, if his estimate is accurate, it means that almost a quarter of children died before reaching age ten. The situation had not greatly improved by the end of the century. A study by the U.S. Institute of Medicine concluded that “in 1900, 30 percent of all deaths in the United States occurred in children less than 5 years of age compared to just 1.4 percent in 1999” (Patterns). What was a dismal and inescapable fact of life for Rebecca Race and her contemporaries has, thankfully, dwindled into rarity today.

Given the change, it is impossible to comprehend the psychological toll such losses created in Rebecca Race's life. How did one face the challenges of raising multiple children while enduring the heartbreak of burying others?

Signer #54 was born Rebecca Turner some time in 1807. Her birthplace is consistently identified as Maine in census records taken during her lifetime. Her father was from Maine, and her mother hailed from Scotland.

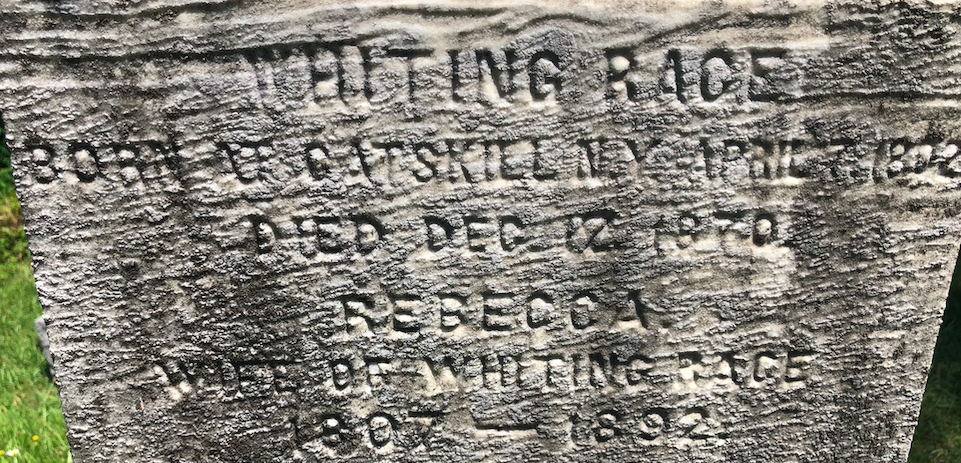

Rebecca married Whiting Race some time prior to 1824, the year they had their first child, Phebe. Born in Catskill, Greene County, in 1802, Whiting was the son of Isaac and Catherine Race (Wellman and Warren 699). As newlyweds, Rebecca and Whiting lived in Catskill and had five more children there: John, born 1825; Helen, 1828; Emeline, 1830; Marsden, 1831; and Catherine, 1833. The Races migrated to Seneca Falls some time around 1834-5, accompanied by Whiting's parents and his brothers, Washburn and Washington (Wellman and Warren 700).

In Seneca Falls, Whiting supported the family by pioneering the local logging industry. Edgar Welch writes that “Whiting Race…had the first lumber yard in town, which occupied the east side of Center street between Canal street and the river on land now owned by the woolen mills company” (59). In a 1905 talk before the Seneca Falls Historical Society, Claribel Teller recalled, “years ago, Whiting Race occupied Dey’s Island, or what was known as ‘Goose pasture’ which was located nearly in the center of the village, as a lumber yard. The island embraces about five acres, and lies between the river and the large race-way which, at that time, was used solely to furnish water power for Chamberlain’s mills” (19). By 1848, part of Whiting's timber yard on Dey's Island was given over to his brother Washburn and Horace Silsby, who used the space to start a business manufacturing pumps, hydrants, and other metalwork (History 46). The river islands that contained Whiting's business have since been submerged as a result of the damming of the Seneca River.

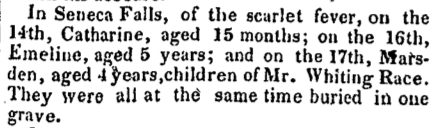

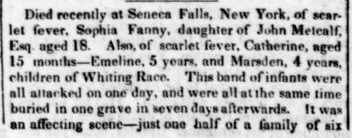

Their initial years in Seneca Falls would be a time of tragedy for Rebecca and Whiting. An outbreak of scarlet fever claimed the lives of their children Catherine, Emeline, and Marsden in the span of only four days, between December 14 and 17, 1835. The three Whiting children fell ill on the same day, passed away within days of each other, and were then interred in the same grave at Restvale Cemetery (Bowman 196). This unforgiving cluster of deaths among the “children of Mr. Whiting Race” warranted mention in The Geneva Courier (“Died”).

As omnipresent as childhood mortality then was, the loss of the three children in such a short order was, nevertheless, reported nationally. During the following February, the Philadelphia-based, weekly Gentleman’s Vade-Mecum lamented that “this band of infants were all attacked on one day, and were all the same time buried in one grave in seven days afterwards. It was an affecting scene—just one half of a family of six children entombed at one burial—one boy and two girls—and one boy and two girls spared to their afflicted parents” (4).

Despite this hardship, the Races prospered economically and continued to grow their family in the coming years. In the 1830s, Rebecca and Whiting welcomed two more children, Carlton, in 1837, and Rebecca, in 1839 (“Whiting Race”). The Race household appears with 5 females and 4 males in the 1840 census for Seneca Falls.

Rebecca and Whiting would also become deeply immersed in the bustling political life of the village. According to the Women's Rights National Historical Park website, Rebecca served as vice president of the local temperance society, headed by Amelia Bloomer (“Rebecca Race”).

Whiting evidently saw eye-to-eye with his spouse on this matter, as William Peck observes that he "was a strong advocate of the temperance cause, doing all in his power to promote the temperance movement” (764). On another front, Whiting was a cofounder of the Seneca County Antislavery Society, inaugurated in 1837, and he later co-founded and became active in the area's abolitionist Free Soil Party in 1848 (Wellman and Warren 28, 210, 234). In 1850, Whiting lent his signature to a petition calling for the eradication of slavery, which was forwarded to Washington D.C. (227). In issues from 1858, 1861, and 1864, The National Anti-Slavery Standard lists Whiting as a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, who had made donations of between $8 and $10 per annum ("Anti-Slavery").

Whiting would also ascend to local political office. Whiting was appointed as one of the trustees of Seneca Falls' First Ward upon the establishment of an amended village charter in 1837. He was later elected president of the village in 1842—the year in which the local fire brigade was first established—and served again as president in 1848, the year of the Convention (History 110). Whiting was evidently a charismatic individual: an 1854 letter from Catharine Paine (Signer #15), who had recently moved west to Seattle, Washington, describes a minister named Brother Roberts, whose enthusiasm brought Whiting to mind. Roberts, Paine writes, “looks very much like Whiting Race and has his gentlemanly and dignified bearing” (108).

One salient detail about the Races' marriage was that it was, evidently, interfaith. Whiting was a Methodist, and Rebecca would remain an Episcopalian for much of her life—although her commitment to temperance activism prompted her to disaffiliate from the Episcopalians and, at least temporarily, join the Presbyterian Church (Peck 764, “Rebecca Race”).

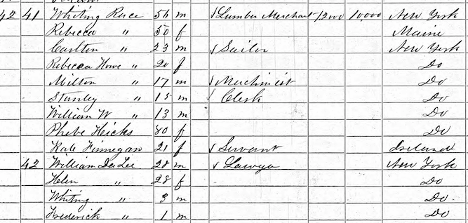

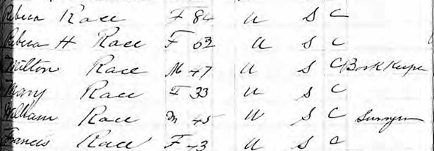

The 1850 census records for the Race household, taken down by Isaac Fuller, shows Rebecca, 42, and Whiting, 46 and a "Lumber Dealer."

Children Helen, 21, and Carlton, 13, live under the same roof. Three more children, Milton, born 1843, Stanley, born 1845, and William, born 1846, have joined the family. The Races are prosperous enough to employ an Ireland-born servant, Ann Ferguson. By 1850, the Races had weathered the passing of two more children. An infant son named Charles lived for six days in 1841. Rebecca's and Whiting's eldest, Phebe, died in 1846 at age 22 (“Whiting Race”). I could find no supporting details surrounding the cause of her death.

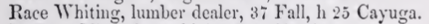

The Races initially lived in a “small gable-end-to-the street Greek Revival house on Green Street, on the south side of the river” in Seneca Falls (Wellman and Warren 209). As Whiting's timber business thrived and the family continued to increase, the Races moved into a spacious, two-story home at 25 Cayuga Street. Brigham’s 1862 directory for Seneca County situates Whiting’s workplace at 37 Fall Street and the Race household at 25 Cayuga (62).

The structure on Cayuga Street still stands, one of only six homes of Declaration signers known to survive, as of 1985 (Weber 172).

The Races appear in the 1860 census, located in the vicinity of Charles L. Hoskins (#85). They live with 5 children, now teenagers and young adults; an Ireland-born servant; and an elderly female, Phebe Hicks, 80, most likely a relative. The teenage males have begun to take up trades: Carlton, 23, is a sailor; Milton, 17, a machinist; and Edwin Stanley, 13, a clerk.

The family’s net worth amounts to $22,000 in assets and real estate. Helen has married one William DaLee, a lawyer, and they reside in the same household with two sons, Whiting and Frederick, 3 and 1.

The family’s net worth amounts to $22,000 in assets and real estate. Helen has married one William DaLee, a lawyer, and they reside in the same household with two sons, Whiting and Frederick, 3 and 1.

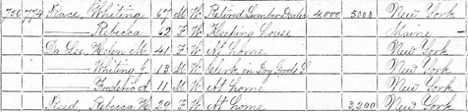

For the 1870 census, Whiting, 67, has retired from the lumber trade, having done so at age 60 (Peck 764). Rebecca, 62, is recorded “Keeping house.”

Married daughters Helen Da Lee and Rebecca Howe Reed reside in the same household, without their husbands and possibly as widows. That year, Whiting Race died on December 12, 1870, at age 68 (“Whiting Race”).

Shortly after Whiting's death, Rebecca moved to Rochester, accompanied by a number of her children, and she would live there for the remainder of her life. In the 1875 census, she resides in the same household as her children Rebecca (now remarried) and Stanley, along with their spouses.

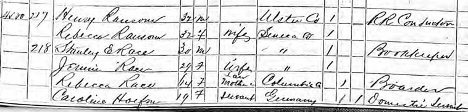

In the 1880 Rochester census, Rebecca Race lives in a household headed by son Edwin. Rebecca’s son William has joined them.

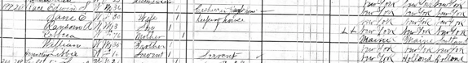

In the 1892 New York census, Rebecca, 84, is listed as head of household. She lives with children Rebecca Howe, Milton, and William, and their spouses. Directories for Rochester in the 1880s and 90s place Rebecca’s home on Chestnut Street (391, 533).

Directories for Rochester in the 1880s and 90s place Rebecca’s home on Chestnut Street (391, 533).

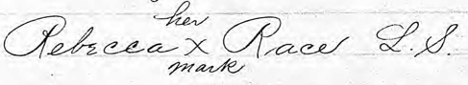

According to the New York Death Index, Rebecca died on July 17, 1895. Her cause of death in Episcopal Church records—she had evidently renewed her relation with that denomination—is recorded as being the result of a fractured hip. Her will, executed in 1891, bears the signature of a legal surrogate and small, faintly drawn “x” indicating “her mark,” put down in her own hand.

Signer #54 is buried in Restvale Cemetery in Seneca Falls on a family plot near the Seneca River. She lies in rest next to her spouse as well as seven of her twelve children, including the three who fell victim to scarlet fever in December 1835. The headstone for daughter Catharine has unfortunately broken loose.

Son Carlton, a sailor, served as a master’s mate aboard the USS Iroquois during the Civil War. He eventually married a woman named Adelaide and moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, working as a clerk. Carlton died on December 10, 1874, at age 37, and he is buried in Minnesota (“Carlton Race”).

Helen married William Da Lee some time prior to 1860 and was likely widowed before 1870. In the 1900 and 1905 censuses, she appears in Rochester. According to her death certificate, Helen had moved to Bay City, Michigan. She died there on November 15, 1909, of heart disease.

Daughter Rebecca Howe Race is remembered by Wilhelmina Brown as an organist at Trinity Church in Seneca Falls (30). She married Henry Ransom in October 1873, and this was probably her second marriage, her surname having changed to "Reed" prior to this (“Married”). She resides with her mother and siblings in Rochester in the 1892 state census. She died in Rochester on April 22, 1897.

Son Edwin married Jane Lay in 1866 and worked as a cashier in the freight office of the New York Central Railroad (Peck 764-5). He died on February 27, 1922, in Paxton, Massachusetts ("Edwin Race").

Son Milton worked as “special deputy commissioner of the excise department” and later as a tobacconist. During the Civil War, Milton joined Company I, of New York’s 19th Infantry and saw combat in Virginia and eastern North Carolina from 1861 to 1863. He received a wound at the siege of Fort Macon, North Carolina. He worked for stretches in Kansas, British Columbia, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, before returning to Rochester. He married Ruth Hill in 1866 (Peck 1276). He died on April 3, 1912, and is buried in Rochester (“Milton Race”).

Son William married one Frances, who passed away in 1895. William worked as a surveyor in Rochester. In the 1900 census, he lives with his brother Milton. He died on March 27, 1901, and is buried in Rochester (“William Race”).

It appears that Rebecca Race soldiered on with life, in spite of the deaths of eight of her twelve children during her lifetime. Being economically advantaged did not exempt the Races from experiencing childhood death within their family.

That Declaration signers eventually became heavily invested in the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP)—including Lucretia Mott (#1) and Charlotte Woodward Peirce (#37)—suggests that advancing the state of medicine, especially the care afforded women, was an implicit element of the Declaration's platform. The harrowing demands of maternity and child-rearing in Rebecca Race's lifetime begged for advancements in the fields of women's medicine, reproductive health, childcare, and public health.

Works Cited

“American Anti-Slavery Society.” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 6 Mar. 1858, p. 3.

“American Anti-Slavery Society.” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 20 July 1861, p. 3.

“American Anti-Slavery Society.” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 17 Dec. 1864, p. 3.

Blaine, David. Memoirs of Puget Sound: Early Seattle, 1853-1856, The Letters of David & Catherine Blaine. Ye Galleon Press, 1978.

Bowman, Fred. 10,000 Vital Records of Western New York, 1809-1850. Genealogical Publishing, 1985.

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Brown, Wilhelmina. “Choirs of Seneca Falls.” Papers Read Before the Seneca Falls Historical Society for the Years 1911-2. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1913, pp. 29-32.

“Carlton Race.” Registers of Officers and Enlisted Men, 1861-1865. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Carlton Race.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 23 May 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/140519716/carlton-whiting-race.

“Died.” Geneva Courier, 30 Dec. 1835, p. 3.

“Died Recently.” Gentleman’s Vade-Mecum, vol. 2, no. 59, 1836, p. 4.

“Edwin Race Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Edwin Race-Death.” Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Helen Da Lee Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Helen Da Lee Household.” New York Census, 1905. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Helen Da Lee – Death Certificate.” Bay City, Michigan 1909. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Henry Ransom Household.” New York Census, 1875. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

History of Seneca Co., New York. Everts, Ensign & Everts, 1876.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Patterns of Childhood Death in America. National Academies Press (US), 2003, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220806/.

“Married.” Geneva Courier, 15 Oct. 1873, p. 3.

“Milton Race Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Milton Race.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 23 May 2022. findagrave.com/memorial/149256514/milton-race.

Peck, William Farley. History of Rochester and Monroe County, New York: From the Earliest Historic Times to the Beginning of 1907. Pioneer Publishing Company, 1908.

“Rebecca Race.” Women's Rights National Historic Park, NPS.Gov, Accessed 23 May 2022. https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/rebecca-race.htm.

“Rebecca Race Household.” New York Census, 1892. Rochester, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Rebecca Race.” New York Wills and Probate Records, 1891. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

"Rebecca Race." New York State Death Index, 1895. Ancestry.com. Accessed 5 May 2022.

"Rebecca Race." New York, U.S., Episcopal Diocese of Rochester Church Records, 1800-1970. Ancestry.com. Accessed 5 May 2022.

“Rebecca Race.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 23 May 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/149248793/rebecca-race.

“Rebecca H. Ransom.” New York State Death Index, 1897. Ancestry.com. Accessed 5 May 2022.

Rochester, New York, City Directory. Drew Allis, 1885.

Rochester, New York, City Directory. Drew Allis, 1894.

Steckel, Richard H. “The Health and Mortality of Women and Children, 1850-1860.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 48, no. 2, 1988, pp. 333–45.

Teller, Claribel. “An Historical Sketch of Horace Silsby.” Papers Read Before the Seneca Falls Historical Society for the Year 1905. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1905. pp. 18-21.

Weber, Sandra. Special History Study, Women’s Rights National Historical Park, Seneca Falls, New York. National Park Service, 1985.

Welch, Edgar Luderne. ‘Grips’ Historical Souvenir of Seneca Falls, N.Y. Grip, 1904.

Wellman, Judith, & Tanya Warren. Discovering the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820-1880. Seneca County, 2006.

“Whiting Race Household.” Federal Census, 1830. Catskill, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Whiting Race Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Whiting Race Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Whiting Race Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Whiting Race Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 23 May 2022.

“Whiting Race.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 23 May 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/149248791/whiting-race.

“William Race.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 23 May 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/149256513/william-w-race.