Signer #82, William Burroughs: "The Last Search"

Best Candidate, Signer #82: William Burroughs

Born: July 19, 1828, Varick, Seneca County

Died: November 24, 1901, Morgan Mill, Texas, age 73

Occupations: Lawyer, Farmer, Notary Public, County Supervisor, Tax Collector, Postmaster

Local Residence(s): East Varick, Seneca County; Waterloo, Seneca County

Special thanks to Lorie Dalola for the research assistance provided in the creation of this piece.

"Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more; Or close the wall up with our English dead." —Shakespeare, Henry V

The search for information about Signer #82 turned up an extensive biography produced during his lifetime. This appears, of all places, in the 1896 History of Texas. Something shocking arose in my eleventh-hour, final round of searching for traces of William Burroughs' life in Texas. I was hoping to uncover his signature or a photograph to finalize the profile. What I found, instead, were accounts of his criminal indictment and subsequent suicide. This last batch of search-results overturned all my previous assumptions about him.

********************************

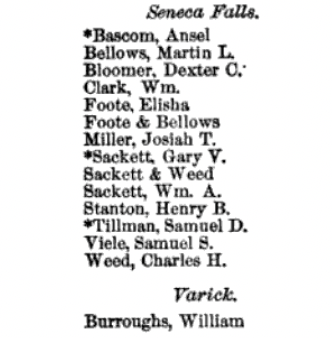

Livingston's Law Register for the year 1853 reveals just how much communal connections drove participation in the Seneca Falls Convention. Livingston's, which advertises itself as an index of "every Lawyer and Firm in the United States," happens to contain an abbreviated who's who of the Declaration of Sentiments (5).

Livingston's listing for Seneca Falls includes Convention participant Ansel Bascom, a prominent local politician. Dexter Bloomer, spouse of Amelia Bloomer, is present as well. So is William Clark, the future spouse of Susan Quinn, Signer #33. Elisha Foote is Signer #72 and the husband of Eunice Newton Foote, Signer #5. Henry Brewster Stanton is the spouse of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Signer #4. Samuel D. Tillman is Signer #70 (168).

Just below, a lone lawyer is given for nearby Varick, William Burroughs. The entry is largely unchanged for the 1854 edition of Livingston's, but a second attorney has joined Burroughs in Varick, the best candidate for Signer #87, Saron Phillips (182):

The abundance of lawyers among the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments reflects the overt legal challenge being mounted in the document. The Declaration was, in essence, an argument demanding a fundamental reinterpretation of the nation's founding documents and existing laws. The attorneys who lent their signatures to the Declaration seem to signal that this legal argument clearly had merit. One unexpected wrinkle to the life of William Burroughs is that, by the summer of 1848, he was not yet barred as an attorney. Nonetheless, the future ties that William Burroughs would have with the legal establishment of Seneca Falls reveal how professional bonds—even aspirational ones—fostered involvement in the Convention.

It should be acknowledged that a second William Burroughs, a farmer born in Cayuga County in 1825, lived in the vicinity of Seneca Falls for his entire life. In the 1850 census, this William Burroughs appears as head of household in nearby Fayette, Seneca County. He would die in 1903 in Seneca Falls and is interred at Restvale Cemetery (“William Burroughs II”). Neither of the two William Burroughs seems to have found much use in a middle name. More maddeningly still, they were married to spouses named Lucinda and Lucy Ann, respectively.

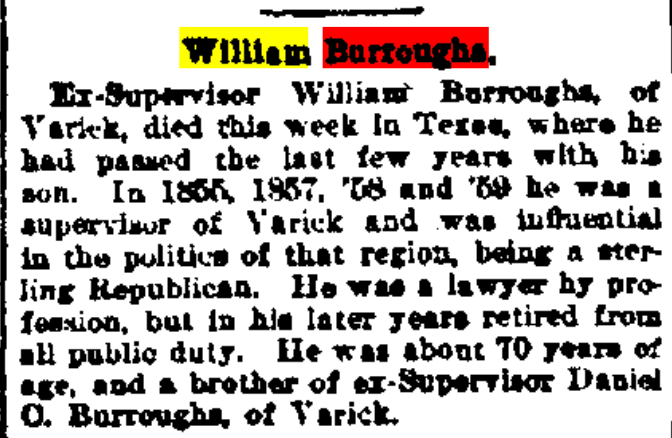

Notwithstanding his namesake, William Burroughs the lawyer had an extensive presence in progressive circles, and a Rochester newspaper would later describe him as being both "influential in the politics" of Seneca County and as "a sterling Republican" ("Burroughs"). Moreover, he was affiliated with the Methodist Church, receiving advanced theological training at two Methodist seminaries. With a law office located on Fall Street, he would remain a fixture of civic life in Seneca Falls for much of his adulthood. He would even name his second-born son in honor of Abolitionist Charles Sumner. Such telltale signs are hard to ignore. These bits of circumstantial evidence, indicating his radical political predispositions, leave me to concur with Judith Wellman's assessment that William Burroughs, Esquire, is Signer #82 (7).

William was the child of Thomas and Phoebe Christopher Burroughs. Thomas migrated to Seneca County from New Jersey in 1812 to start a farm. He is said to have “drowned in Cayuga lake while returning from entertainment given in Aurora Seminary,” an accident that would have occurred, according to his headstone, in 1868 (Texas 98). The Burroughs family plot at Oak Hill Cemetery in McDuffie Town, Seneca County, also indicates that William had a brother, Thomas Sidney, who was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864 (“Thomas Burroughs”).

William worked on the family farm until 1843, when he enrolled at Waterloo Academy. He then moved on to study at two Finger Lakes religious institutions, Genesee Wesleyan Seminary in Lima and Cazenovia Seminary in Madison County (Texas 98). Cazenovia Seminary records that a William Burroughs of Romulus, Seneca County, was in attendance during 1846 (418).

William's matriculation at these schools is said to have each lasted a year, “after which he returned to the old homestead and aided in its cultivation for two years” (Texas 98). This homecoming would have put William back in Seneca County in time for the Convention. Unmarried by the summer of 1848, William Burroughs is only the second bachelor present (so far) in the Declaration of Sentiments, the other being Justin Williams, Signer #71. Opting to resume his education yet again, William relocated to Ballston Spa, Saratoga County, to study law at the State and National Law School. He was admitted to the New York State Bar in 1851. On February 24, 1853, William married Lucinda Beary from nearby Bearytown (Texas 98).

Initially, William dabbled in local politics, taking on work as a county supervisor representing Varick in the second half of the 1850s (Child 109). He also politely declined a nomination to campaign as the Republican candidate for district attorney in early November 1859. The Ovid Bee reports that, during a county convention, “William Burroughs, Esq. the most prominent candidate, refused a nomination; and our friends were compelled to go outside the recognized members of the profession,” selecting a local “school-master” instead (“Ticket”).

William, 31, and Lucinda, 27, appear in the 1860 census for Varick, and the family’s wealth is assessed at $2,000. A son Thomas is four years old, and a newborn son, Charles Sumner, is three months.

Brigham’s 1862 directory lists William as a resident of Varick. A commuter, his law office is located at 72 Fall Street in Seneca Falls (78).

The Central New York Business Directory for 1861 further specifies that Burroughs' office is located near the corner of Fall and Cayuga, just a few doors down from William Clark (145). Child’s 1867 county directory advertises William Burroughs' services in the capacity of notary public (224). And, from 1862 to 1868, he also served as a tax collector (Texas 98).

In the 1870 census for Varick, William and Lucinda live with five children: Thomas, 14; Charles Sumner, 10; Emma, 8; Grace, 5; and a one-month-old named Laura. The family’s wealth in real estate is valued at $5,500, and their personal effects, entered on Lucinda’s line of the census, amount to $600.

The 1904 “Grips” Historical Souvenir attests that William practiced law until 1871, leaving the profession for reasons that are unclear (108).

By 1880, William has transitioned into farming. Six children live with Lucinda and William in Waterloo: Thomas is 24 and a "Tree Agent"; Charles, 20, is helping out on the farm. Emma and Grace, teenagers of 19 and 16, respectively, have begun work as teachers. Daughter Laura is 9, and a son, Leroy, 7, has joined the fold.

The last trace I could uncover of William Burroughs' presence in Seneca County is an appearance in The Waterloo Observer from September 1889. He delivered an oration at a political meeting in support of the reelection of State Senator William Sweet, a native of Waterloo. William's oration confirmed his “high reputation as a brilliant and thoughtful orator by his intelligent and electric speech” (“Local”).

William and Lucinda would move to Morgan Mill, Texas, in 1890, where William had the initial goal of starting a new law practice. The couple followed their son Charles Sumner to Texas. He had migrated there in 1882 and worked on the railroads before becoming a merchant and farmer. In 1892, William was appointed postmaster of Morgan Mill "by President Harrison," The History of Texas proudly observes (98).

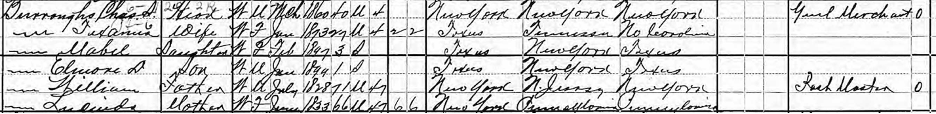

In the 1900 census, William and Lucinda appear in the household of Charles Sumner Burroughs in Erath County, Texas. Now 71, William's occupation is listed as "Post Master." In response to the harsh question asked in the 1900 census, Lucinda responded that, of the six children she had given birth to, six were still alive.

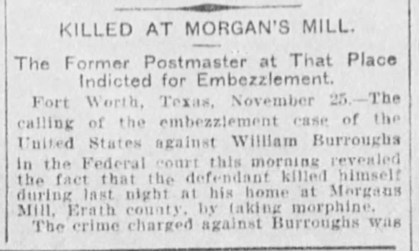

At some point in 1901, William was accused of embezzlement. The precise details of this allegation are unclear, but it was alleged that William had stolen government funds while serving in his capacity as postmaster some time in January 1901. William was indicted by a federal grand jury before being released on bond. Pending trial, William is said to have attempted suicide a number of times. He died by his own hand on November 24, 1901, at Morgan Mill, overdosing on morphine ("Killed").

His death was covered in The Houston Post and The Dallas Southern Mercury ("State News"). William is buried in the Morgan Mill Cemetery (“William Burroughs”). A positive obituary was run in New York by The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle on the occasion of his passing. It makes no mention of the unfortunate events that had occurred in Texas.

Of course, the circumstances of William's death raise a number of questions about the crime for which he was being prosecuted. Beyond what's recorded in two newspaper articles, I could not obtain further details regarding the charges against him. With decades of experience as a lawyer, why did William choose not to defend himself against these accusations? It also stands to reason that William's advanced age might have been an ameliorating factor in trial deliberations and in sentencing (in the event that he was found guilty).

Now widowed, Lucinda went back east and appears in the 1910 census in Varick, living on the farm of her son Leroy. Lucinda would pass away in March 1915 at age 81. She spent her last days in the home of daughter Emma Burroughs Emens. An obituary for Lucinda in The Seneca County Courier-Journal recalls her spouse favorably: “many of our older residents will remember William Burroughs, who fifty years ago was a popular lawyer in this county, having at one time an office in Seneca Falls” (“Romulus”). Lucinda is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in McDuffie Town (“Lucinda Burroughs”).

Of William Burroughs’ children, The History of Texas places son Thomas in New London, Connecticut. Charles Sumner remains at Morgan Mill and would succeed his father as postmaster. Emma has returned to her mother’s birthplace, Bearytown, New York. Grace is a professional nurse residing in Rochester. Laura May lives in Cleveland, Ohio, and LeRoy is in Seneca County. Emma Burroughs Emens lived to 1919 and is buried in McDuffie Town. Thomas lived in Connecticut, passing away in 1941 at Deep River ("Thomas Burroughs"). Grace lived until 1953. She was 88 and is now buried in Glendale, California ("Grade Burroughs"). Charles died in 1946, at age 85, and is buried in Dallas, Texas ("Charles Burroughs"). According to her death certificate, Laura Burroughs Dahn would pass away at age 70 in October 1940, a resident of Coldwater, MIchigan.

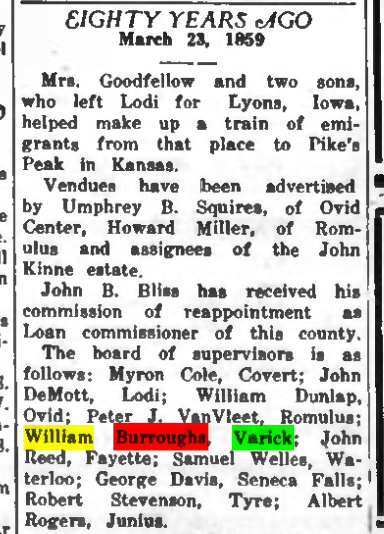

One odd feature of William Burroughs’ life story after his mysterious death is his repeated mention in 20th-century Finger Lakes newspapers, which happen to be running "time capsule" articles on regional history from the previous century. Take, for example, this mention of William from March 1939 in The Ovid Gazette and Independent, recounting the news of the same calendar day exactly 80 years prior. William is identified as one of the Board of Supervisors for Varick (“Eighty”).

In 1955, The Gazette would rehash the news of 1855, again naming William as a county supervisor 100 years earlier (“100”).

In 1955, The Gazette would rehash the news of 1855, again naming William as a county supervisor 100 years earlier (“100”).

Judith Wellman has argued that social networks are key to understanding the identities and motives of those in attendance at the Seneca Falls Convention. Religious, political, and familial connections most certainly tie these individuals together in an intricate, overlapping communal web. The disproportionate number of lawyers who became signatories of the Declaration of Sentiments indicate that professional networks are also key to understanding the lives of the 100 signers. The names of lawyers in the Declaration signal that these men supported the cause being articulated at the Convention and the future legal battles it would engender.

As for William Burroughs, a final search for artifacts from his life uncovered unsettling information about his indictment and death. These events should inform, but not overshadow, his biography and his radical support for women's civil rights at the Seneca Falls Convention. William Burroughs' life—like everyone's—was complicated.

Works Cited

“100 Years Ago.” Ovid Gazette and Independent, 1 Apr. 1955, p. 3.

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

"Burroughs Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Fayette, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

"Burroughs Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Varick, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

"Burroughs Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Varick, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

"Burroughs Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Waterloo, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

"Burroughs Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Erath County, Texas. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

"Burroughs Household.” Federal Census, 1910. Varick, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

“Charles Burroughs.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39264218/charles_sumner_burroughs.

Child, Hamilton. Gazetteer and Business Directory for Seneca County for 1867-8. 1867.

“Eighty Years Ago.” Ovid Gazette and Independent, 17 Mar. 1939, p. 4.

"Emma Burroughs Emens." Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/153263276/emma-d-emens.

The First Fifty Years of Cazenovia Seminary, 1825-1875. Nelson & Phillips, 1877.

“Grace Burroughs.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/85359284/grace_burroughs.

‘Grips’ Historical Souvenir of Seneca Falls, N.Y. Grips, 1904.

History of Texas, Supplemented with Biographical Mention of Many Families of the State. Lewis, 1896.

Hutchinson, Thomas. Central New York Business Directory. Hutchinson, 1861.

"Killed at Morgan's Mill." The Houston Post, 26 Nov. 1901, p. 3.

“Laura Burroughs Dahn—Death Certificate.” Michigan Department of Health, 1940. Livingston, John.

Livingston, John. Livingston’s Law Register for 1853. Office of the Law Magazine, 1853.

Livingston, John. Livingston’s Law Register for 1854. Office of the Law Magazine, 1854.

“Local News.” The Waterloo Observer, 4 Sep. 1889, p. 1.

“Lucinda Burroughs.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39059809/lucinda_burroughs

“The Republican Ticket.” The Ovid Bee, 2 Nov. 1859, p. 1.

“Romulus.” Seneca County Courier-Journal, 18 Mar. 1915, p. 8.

"State News." The Dallas Southern Mercury, 28 Nov. 1901, p. 11.

“Thomas Burroughs.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39054870/thomas_b_burroughs

"Thomas Burroughs II." Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/70023165/thomas_edson_burroughs

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“William Burroughs.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/19468924/william-burroughs.

“William Burroughs II.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 25 Apr. 2024. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/245658221/william-burroughs.

“William Burroughs.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 12 Dec. 1901, p. 4.