Signer #87, Saron Phillips: “The Lockout"

Best Candidate, Signer #87: Saron Phillips

Born: April 25, 1820, New York State

Died: January 21, 1862, Varick, Seneca County, age 42

Occupations: Lawyer, farmer, public servant

Local Residence(s): Varick, Seneca County; Romulus, Seneca County; Romulusville, Seneca County

Thanks to Mayra Castillo Gonzalez for research assistance provided in the production of this piece.

A piece of eyewitness testimony provides a vital clue about one person who was likely not to be on hand at the opening of the Seneca Falls Convention. On the morning of Wednesday, July 19, 1848, the crowd assembled at the Wesleyan Chapel allegedly found itself locked out of the building. As Charlotte Woodward Peirce (Signer #37) recalled in 1919, Daniel Cady Eaton, the 11-year-old son of Harriet Cady Eaton (#2), seized the initiative and shimmied through an open window to unlock the doors from inside (Dorr 23). Whether the church had been sealed off by accident or with some passive-aggressive intent, we will never know.

It is unclear if Peirce directly observed this moment or if it consists of a bit of secondhand gossip she later caught wind of. Perhaps it amounts to nothing more than some apocryphal hearsay that had survived in her memory for more than seven decades. But, if the story of the lockout happens to be true, it suggests that there was one person who was probably not in attendance that day. It is the person most likely to have a key to the church: its pastor.

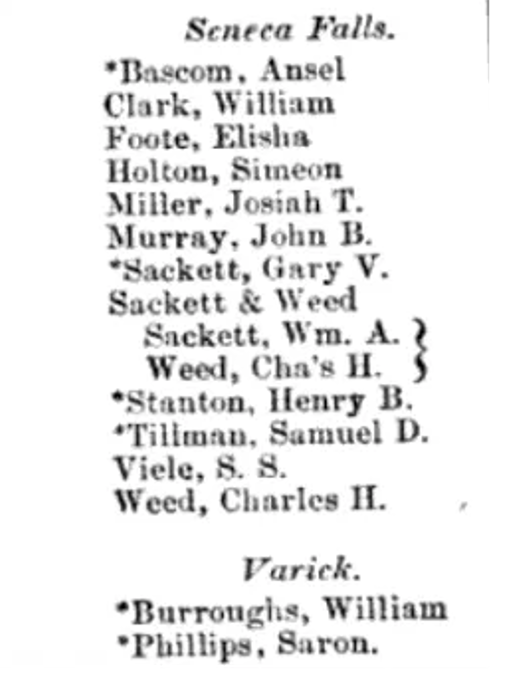

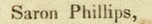

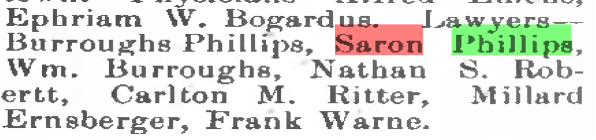

Present-day scholarship on the identity of Signer #87 has repeatedly argued that this individual must have been the minister of Wesleyan Chapel, the Methodist church that hosted the Seneca Falls Convention. My recent research into the lawyers who signed the Declaration of Sentiments, namely Samuel D. Tillman (#70) and William Burroughs (#82), has alternately revealed a more-viable candidate. The 1854 edition of Livingston's Law Register identifies one Saron Phillips as a Seneca County attorney, based out of the rural hamlet of Varick (182).

Varick is a located on the strip of land between Seneca Lake and Cayuga Lake, 11 miles to the south of Seneca Falls. Because of the extreme rarity of the given name “Saron,” I am inclined to argue that this individual is Signer #87. By the same token, evidence exists indicating that the minister of the Wesleyan Chapel in 1848 was known as "Samuel Phillips," not Saron.

The origin of this error can be traced to a misinterpretation of one source in particular, The Manual of the Churches of Seneca County with Sketches of their Pastors, 1895-6. The text is an extensive history of the various houses of worship in the region, with chapters arranged by Christian denomination. It includes the names of prominent Seneca church leaders and parishioners, both past and present. One "S. Phillips" is named as the pastor of the Methodist church in Seneca Falls. Phillips held the position beginning in 1847 until being replaced in 1849 (171). This individual’s full first name is never given the volume.

Since S. Phillips presided over the Wesleyan Chapel at the same time as the Seneca Falls Convention, it has been presumed that he must be Signer #87.

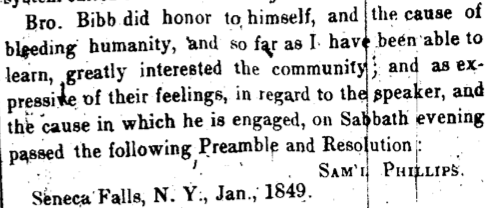

Pushing back on this conclusion, Sharon Brown was able to uncover some proof of what the “S.” actually stood for. Brown’s structural report on the Wesleyan Chapel from 1987 cites an 1849 letter printed in The True Methodist, a denominational newspaper.

Addressed to editor Luther Lee, the letter describes a lecture delivered by Abolitionist Henry Bibb on January 19, 1849. The event was held at “the Great Light House of Seneca Falls, known as the Wesleyan Chapel, or Anti-Slavery Depot.” The sanctuary also evidently had a poor reputation among anti-abolitionists, one of whom called it “some few years since, the Devil’s Depot.” Henry Bibb, here “Bro. Bibb,” orated to a packed house for two hours “on the importance of sending the Bible to the Slave, the down-trodden of this land” ("Bibb"). Bibb’s autobiography, The Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, would be self-published later that same year.

Regarding Bibb’s reception that day, “the audience listened with profound attention to the tale of his sufferings, during the twenty-five years of his chattelhood, and from appearances, we should judge, he produced in the minds of his hearers, a deep hostility to the accursed system called American Slavery!” A “Preamble and Resolution” were subsequently circulated among those present, who could vote in support of the document's demands. This act is, of course, reminiscent of similar events from the previous summer. The similarity between Bibb's resolution and the Declaration of Sentiments imparts some sense of the modes of activism that the Wesleyan Chapel attracted.

The letter writer signs off as “Sam’l Phillips,” a shorthand of the name “Samuel.” Samuel Phillips does not explicitly identify himself here as the clergyman attached to the Wesleyan Chapel. His familiar, fraternal tone with the editor of a Methodist periodical, addressed here as "Dear Brother Lee," implies that they hold similar station and are of likeminded political orientation. And, if he introduces himself here as “Samuel Phillips," it seems highly unlikely that he had self-identified variantly as “Saron Phillips” in the Declaration six months prior.

It has been argued in this blog that misread versions of signers' names do appear in the reproduction of the Declaration of Sentiments printed at The North Star in Rochester. The Report of the Woman's Rights Convention is invaluable because no original copy of the Declaration is known to have survived. I have argued that transcription errata did occur for the names of less-prominent, local attendees, like Mary S. Mirror (#34) and Robert Smallbridge (#83). But, to somehow mistake a handwritten signature bearing the very common name “Samuel” for the much rarer “Saron” seems inconceivable.

Saron Phillips, the Varick lawyer, leaves behind a few traces that offer a glimpse into his life and character. The birthdate given on his tombstone is April 25, 1820, and his birthplace is identified in a census record as New York State ("Saron Phillips"). Some evidence of his early education in Seneca Country appears in local newspapers, albeit long after his lifetime. In 1899, The Ovid Gazette and Independent ran an article about the annual reunion of McDuffeetown School. McDuffeetown is essentially a neighborhood of Varick. A Saron Phillips is touted as one the institution's distinguished alumni who served on McDuffeetown's school board and as inspector of common schools ("Reunion")..

A list of school graduates who later became lawyers includes Saron Phillips and “Wm. Burroughs.” This was the first in a number of overlaps in the lifelines of Saron Phillips and the best candidate for William Burroughs, Signer #82.

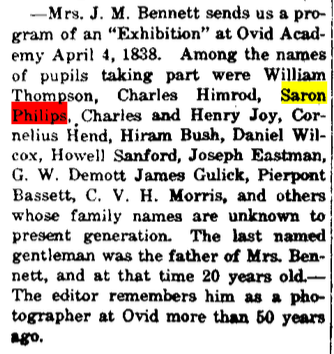

Elsewhere, in 1923, The Interlaken Review relates that one of its subscribers has sent the newspaper a program from an “Exhibition” held at Ovid Academy in April 1838. A Saron Philips is listed among the students presenting, among “others whose family names are unknown to the present generation” (“Interlaken”).

I felt compelled to look into the origin of the name Saron, which, as it turns out, has both biblical and classical roots. It is a Greek variation of “Sharon,” which hails from the Hebrew meaning “his plain” or “his song.” Saron/Sharon appears frequently in place names of the Old Testament (Hitchcock 17, 18, M’Clintock 358). Ancient Greek myth also contains a Saron, “a king of Corinth” who “perished at sea, and was made a sea god” (Mayo 384). King Saron died hunting a deer; in its flight, the animal plunged off a cliff and into the sea. By accident, the king chased after and fell to his death as well (385).

During the 1840s, Saron Phillips surfaces holding several low-level public offices in Varick. In February 1846, Varick has approved a payment of $9.38 for services he rendered as a marshall (“Varick Co.”). In April 1846, The Ovid Bee reports that Saron Phillips has been appointed as an election inspector for Varick, representing the Whig Party (“Inspectors”). In April 1848, he has secured the office of Whig justice (“Result”). In December 1849, he is mentioned having served in the capacities of “justice” and “district clerk.” He has been paid an amount of $1.50 for this labor this time (“List”). In January 1850, Saron Philips is recognized as one of four justices, responsible for supervising the administration of Varick’s public finances (“Board”). In 1847, The National Anti-Slavery Standard lists Saron Phillips of Romulusville as a subscriber (“Acknowledgements”).

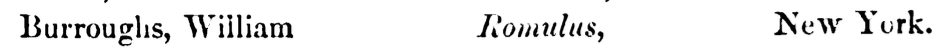

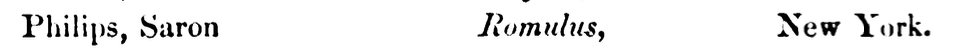

A “Saron Philips” who hails from Romulus, New York, appears as a junior in the 1851 class roster for the State and National Law School, located at Ballston Spa, New York (20). Sullivan Ballou of Woonsocket, Rhode Island, who later became famous for the heartfelt letters he penned to his wife during the Civil War, is listed as “Sullivan Ballon” in the same directory (15). The best candidate for Signer #82, a William Burroughs from Romulus also appears as a senior (15). Romulus is a municipality approximately two miles from Varick.

Phillips and Burroughs' matriculation to the short-lived law school around this time might help to explain their mutual absence from Seneca County for the 1850 census.

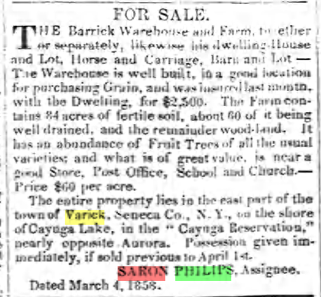

In March 1858, Saron Philips appears in The Waterloo Observer as assignee, basically, the agent of sale, in an advertisement for a piece of Varick farmland located on Cayuga Lake ("Sale").

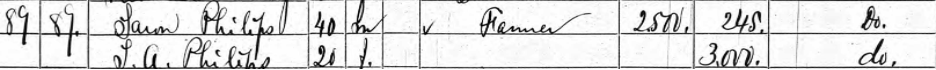

In the 1860 census, Saron Philips, now 40, appears in Varick. His occupation is given a farmer, and his worth is assessed at $2,745.

A 20-year-old female named S.A. Philips resides with him. Her worth is assessed at $3,000. Without a full name to search for, the identity of S.A. Philips must remain a mystery.

The non-population schedules taken for the 1860 census additionally reveal that Saron Phillips owns a 43-acre farm in Varick, appraised at $2,500. He owns a single horse with no other livestock, and he grows corn and oats on the land.

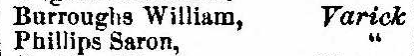

William Burroughs and Saron Phillips would continue to be Varick’s only attorneys throughout the 1850s. The New York City Business Directory for 1859, which includes statewide professional listings, lists the two country lawyers (484).

According to the date inscribed on his tombstone, Saron Phillips died on January 21, 1862, at age 42. He is interred at Oak Hill Cemetery in McDuffietown, Seneca County (“Saron Phillips”). His cause of death is not known.

Charlotte Woodward Peirce’s anecdote about the lockout is not definitive proof that Reverend Samuel Phillips was not a participant in the Seneca Falls Convention. But, acknowledging the preponderance of lawyers in the Men's Section of the Declaration of Sentiments, it is hard to ignore the fact that someone actually named "Saron Phillips" lived in Varick, just a handful of miles away from the Wesleyan Chapel.

Adopting a localized, grassroots perspective is crucial to understanding the people who took part in the Seneca Falls Convention. As Judith Wellman has argued, social networks drove personal involvement in the event. Those same social networks are a critical tool for uncovering the lives of the signers. Saron Phillips' biography shares several points of intersection (occupational, geographical, and educational) with the another best candidate, William Burroughs. Because the name Saron was as unique in 1848 as it is today, it must be said that Saron Phillips is the best candidate for Saron Phillips, Signer #87.

Works Cited

“Acknowledgements.” National Anti-Slavery Standard, 11 Feb. 1847, p. 147.

“Annual Reunion and Picnic of Alumni Association of the McDuffeetown School—Historical Paper.” Ovid Gazette and Independent, 1899. Fulton history.com, https://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html. Accessed 5 April, 2025.

Bibb, Henry W. Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave. Self-published, 1849.

“Board of Auditors.” The Ovid Bee. 23 Jan. 1850, p. 1.

Brown, Sharon A. Historic Structure Report: Historical Data Section, Wesleyan Chapel, Women’s Rights National Historical Park, New York. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987.

Catalogue and Circular of the State and National Law School at Ballston Spa, N.Y. Johnson & Davis, 1851.

Dorr, Rheta Childe. “The Eternal Question.” Colliers, The National Weekly, 30 Oct. 1920, pp. 5-6, 23-24.

“For Sale.” The Waterloo Observer, March 1858. Fulton history.com, https://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html. Accessed 5 April, 2025.

Hitchcock, Roswell D. Hitchcock's New and Complete Analysis of the Holy Bible. A.J. Johnson, 1870.

“Inspectors of Elections.” The Bee (Ovid, New York), 7 Apr. 1847, p. 1.

“Interlaken and Vicinity.” Interlaken Review, 22 June 1923, p. 1. https://fultonhistory.com/Fulton.html. Accessed 5 April, 2025.

“A List of the Names.” The Ovid Bee, 19 Dec. 1849, p. 1.

Livingston, John. Livingston’s Law Register for 1853. Office of the Law Magazine, 1853.

Livingston, John. Livingston’s Law Register for 1854. Office of the Law Magazine, 1854.

Manual of the Churches of Seneca County with Sketches of their Pastors, 1895-6. Courier Printing Co., 1896.

Mayo, Robert. A New System of Mythology: In Three Volumes, Giving a Full Account of the Idolatry of the Pagan World. Vol. 3. Self-published, 1819.

M’Clintock, John and James Strong. Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. Vo1. Harper & Brothers, 1880.

New York City Business Directory. 1859.

Phillips, Samuel. “Henry Bibb, the Fugitive.” The True Wesleyan, 10 Feb. 1849, p. 22.

“Philips Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Varick, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 March 2025.

“Phillips Household” Federal Census Non-population Schedules, 1860. Varick, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 25 March 2025.

“Result of Town Meetings.” Ovid Bee, 12 Apr. 1848, p.1.

Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19th and 20th, 1848. John Dick, 1848.

“Saron Phillips.” Findagrave.com, Accessed March 12, 2025. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/153317738.

“Varick Co. Bills.” The Bee (Ovid, New York), 11 Feb. 1846, p. 1.