Signer #14, Delia Mathews: "The Dissenter"

Signer #14, Delia Bellows Mathews

Born: March 23, 1797, Hebron, New York

Died: January 21, 1883, Seneca Falls, Age 85

Occupation: “Keeping House”

Local Residences: 20 Center Street, Waterloo; Ovid Street, between Chapin and Barker, Seneca Falls

Elizabeth Cady Stanton begins her Seneca Falls Address with the admission that she was knowingly in violation of a long-held taboo: “I should feel exceedingly diffident to appear before you at this time, having never before spoken in public.” This acknowledgement does not constitute hyperbole on her part. A very real convention then existed that discouraged women's public speech. A special type of infamy was reserved for those women who spoke before “promiscuous” audiences, meaning mixed groups that consisted of both men and women. Circumventing the prohibition against speaking in public, women found alternative means of exercising and expressing agency. One of these involved church choice, that is, switching religious and denominational affiliations in order to find a church organization that squared with one’s personal positions on any number of matters. Women also cultivated influence within a particular religious community as another method of making their voices heard.

The life of Delia Bellows Mathews, Signer #14, embodies this idea. She was part of a splinter group that tried repeatedly to establish a Congregationalist church in Seneca Falls. Since she could not speak aloud, Signer #14 worked to build a church (and a pulpit) that matched her deeply felt personal beliefs about temperance, abolition, and women’s rightful involvement in civic life. This practice, of transitioning between churches, most certainly created hardships in Delia Mathews’ life. In 1843, she became embroiled in a “great conflict” within the local Presbyterian church, an incident related directly to the debate over the right of women to speak out against slavery (History 114). Her role in the matter, ironically, called for Delia Mathews to speak publicly, like Stanton, as a challenge to that cultural norm.

According to Thomas Bellows Peck’s The Bellows Genealogy (1898), Delia Bellows was born on March 23, 1797, the tenth of Thomas Bellows’ and Deliverance Button’s eleven children. Thomas was a Revolutionary War veteran and justice of the peace who “never got more than one dollar for a marriage fee” (“Thomas Daniel Bellows,” Peck 607-8). Her mother’s name “Deliverance” suggests that Delia's lineage hailed, in part, from the New England Puritans—a tradition that is echoed in the name of Delia’s elder sister “Thankful,” born in 1791 (Peck 608). In a 2017 post, I examined the Puritan roots evident in the name of Signer #65, Experience Gibbs, and asked how a Puritanical heritage resonated in the Seneca Falls Convention more broadly. Indeed, the spirit of the New England Puritans would echo throughout Delia Mathews’ life, in her changing church affiliations and in the controversy of 1843.

Thomas and Deliverance moved to New York from Connecticut more than a decade prior to Delia’s birth. Peck writes, “About 1779, Thomas, with wife and two or three children and three horses, made his way from Preston, Ct., to Hebron, N.Y., and lived there until 1808, when he went to Salem, N.Y.” (607-8). Hebron, Delia’s birthplace, is situated on New York’s border with Vermont; Salem sits just a few miles to the south.

In 1817, Delia wed Jabez Mathews (also Matthews, Matthew), a native of Massachusetts, born circa 1795 (“Mathews-Bellows Marriage”). I came across a number of records that indicate that Jabez was a veteran of the War of 1812. Of these, a handwritten 1857 “War Declaration,” initiated by Jabez in Waterloo, attests that he was a sergeant in an infantry regiment under the command of Captain James Harkness and one Colonel Root. Jabez served during the month of September 1814, and he personally outfitted himself using his own clothing, gear, firearms, and ammunition, worth an estimated total of $35.25. The “War Declaration” enumerates that he was not paid in cash for his month-long tour of duty. He was, it states, otherwise awarded with 160 acres for his service, possibly supplying some explanation for the Mathewses’ migration west, to the Finger Lakes Region. The militia that Jabez served in was activated in defense of Salem, Washington County, where Delia spent her teenage years. Jabez’s war record, placing him in Salem, helps to explain how the couple might have met. A list of Seneca Falls pensioners, published by the U.S. Senate in 1883, indicates that Jabez, a "surv. 1812," was awarded an $8.00 monthly pension beginning in 1878 (407).

It is unclear exactly when Delia and Jabez moved to Seneca Falls, but Delia’s parents migrated there from Salem in 1821 (Peck 608). Thomas Bellows died in 1833, age 80, and Deliverance Bellows lived to be 89, passing away in 1844. Both Thomas and Deliverance are interred in the Old Ovid Street Cemetery of Seneca Falls (“Deliverance Bellows,” “Thomas Bellows”). Delia's elder brother, Matthias Button Bellows, also took up residence in Seneca Falls, working in the village as a physician (Jordan 497).

Delia and Jabez became members of Seneca Falls' Presbyterian congregation in 1826 and 1830, respectively (Altschuler & Saltzgaber 84). This order suggests that Jabez followed Delia’s lead in joining the church. The couple’s commitment to Presbyterianism, however, was short lived and ill fated. The 1876 History of Seneca County recalls that “Mr. and Mrs. Jabez Mathews” were part of a group that seeded a Congregationalist church in the village during 1834. This pilot Congregationalist community gestures to a larger rift within the Presbyterian church nationwide during this period. Structurally, the Congregationalists are said to disperse self-governance out more broadly to the larger polity of the church, as the Presbyterian limits governance more narrowly among church elders (Gray & Tucker 1-2). The schism, however, spoke more directly to varying positions on the issue of chattel slavery, with the Congregationalists demanding more direct and public action militating against it (Kling).

The 1834 Congregationalist group constructed a chapel on Bayard Street and attracted between 40 and 60 members. It ultimately failed due to the flagging health of its pastor and an inability to find a suitable replacement for him (History 113). When the Congregationalist church dissolved, its members were reabsorbed into community churches (114). Delia and Jabez were compelled by these events to return to the Presbyterian church.

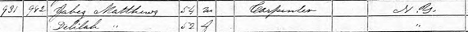

By the time of the 1840 census, Jabez, in his forties, is recorded residing in Seneca Falls with Delia, who appears an unidentified female, also in her forties:

In 1841, Jabez was among a group of 23 village males who organized the Liberty Party, which called for nationwide non-partisan mobilization around the cause of abolition (Wellman 125-6). Abram Failing, a fellow Liberty Party member, was also a former member of the disbanded Congregationalist church, making the root motivations of the Mathewses’ political and religious dissent all the more evident (History 114).

Jabez’s political activities and the couple’s temporary integration within a competing church likely served to create tensions with the Presbyterian church hierarchy. A series of events in 1843 pushed any simmering resentments fully into public view. During the first week of August, nationally renowned abolitionist Abby Kelley traveled to Seneca Falls to give a series of talks, to whip up anti-slavery sentiment and win converts (Wellman 127). Delia and Jabez attended one of Kelley’s orations, given before a mixed audience on the property of Ansel Bascom. Taking an active role, Jabez led the recitation of a hymn at the start of the gathering (Wellman 122). In her speech, Kelley leveled criticism at Northern Protestants, for failing to combat slavery more openly and more intensely. She also took aim at the leadership of area churches and invoked, by name, Seneca Falls’ Presbyterian pastor, Horace Bogue. Alluding to puritanical witch trials, Kelley remarked that “Mr. Bogue would see me burn at the stake, if he had it in his power” (qtd. in Wellman 122). What precise actions caused Kelley to direct her personal attention at Reverend Bogue is unknown, but Bogue had likely made his position on women’s public speech on the topic of slavery very clear to some intermediary.

Local clerical resistance to Kelley’s visit struck a raw nerve among villagers. In October, Bogue was confronted by Rhoda Bement, a temperance organizer and member of the Presbyterian church. Bement had placed anti-slavery materials on Bogue’s desk, and she later asked him if he had taken any notice of them. When Bogue replied that he had not, Bement chastised him on the church’s silence in regard to slavery. The fiery exchange prompted Presbyterian elders to try Bement within the church, threatening her with excommunication. Bogue alleged that Bement had refused to partake of communion wine, had attended Kelley’s orations, and had spoken to him in an unbecoming manner (Wellman 132).

Delia and Jabez both acted as witnesses in Bement’s trial—although Jabez’s testimony was more extensive and clearly given more heft than Delia’s. Called twice to testify during the proceedings, Jabez was asked by the church “Judicatory” if there existed biblical authorization for a woman, like Abby Kelley, to speak before a mixed audience “for the purpose of addressing them on Moral & Religious subjects” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 116). Jabez answered in the affirmative, that there was a biblical basis justifying women’s public speech. When asked “whether he as a Presbyterian considered it proper for a female to call a promiscuous meeting for the purpose of addressing them on Moral & Religious subjects,” Jabez answered, “I do” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 116). When asked if his positions were in harmony with the orthodox conventions of the church, Jabez answered in the negative. In his second testimony, he avowed that he had, in fact, heard Kelley speak “two or three” times at meetings that week. They were, he retorted, “attended with more propriety than some of the Religious meetings in this village” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 116, 117). When asked if Kelley had claimed that northern churches “were guilty of stealing men, women & children,” he assented. He testified that Kelley had argued “that the Northern churches upheld the southern churches in robbing cradles” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 123).

Among a number of female witnesses, Delia’s more-abbreviated testimony was limited specifically to the allegation that the temperance-minded Bement had refused to imbibe communion wine. Delia stated that the church’s wine had become noxious and unpotable for her: “the last I partook of the wine it was very offensive; it was very strong alcoholic wine. I have been absent the last two communions and at the two previous communions I refused to partake of it. Reasons, consciousness” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 106-7). In spite of Delia’s and Jabez’s support, Bement was found in violation and excommunicated. Refusing to confess or repent, she thereafter departed Seneca Falls for Buffalo (Altschuler & Saltzgaber 140, Wellman 134). Her persecutors repeatedly understood Bement’s actions and behaviors more broadly, as her trial evolved into a proxy debate on the divisions within the church, along the fault lines of temperance, abolition, and women’s rights. Without identifying Rhoda Bement by name, The History of Seneca County refers to the events of 1843 instead as “the great conflict on the question of American slavery” (114).

The intra-congregational hostility borne out in Bement’s trial did not go away following her excommunication. Rather, the church’s scrutiny eventually shifted to Delia and Jabez. In September 1845, they were pressured into publically conceding that “they had done wrong” and admitted that “if they had understood their obligations to the church they never would have done what they did” (quoted in Altschuler & Saltzgaber 166-7). Elders stopped short of excommunicating the couple and instead granted a “dismission” that allowed them to re-affiliate with the Congregationalist church in Prattsburgh, Steuben County, more than 40 miles southwest of Seneca Falls (167). Other witnesses who testified on Bement’s behalf were given similar dismissions or were excommunicated themselves (Altschuler & Saltzgaber 82-4). The Bement Affair illustrates how members of the church were, when pressed, willing to challenge discrepancies between their personal beliefs and the more-dogmatic positions of church leadership. And such challenges came at a high, personal cost.

The hardline taken by the church garnered consequences of its own, creating a broader exodus within the congregation, especially among the church’s former Congregationalists. The History of Seneca County notes that “during the great conflict…true to the spirit of the Pilgrims of the Mayflower, many Congregationalists withdrew from the other churches and became identified with the Wesleyan, in 1843” (114). In the aftermath, a number of individuals were drawn to the Wesleyan Chapel, the future site that would play host to the Seneca Falls Convention.

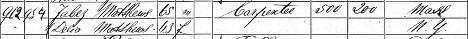

During their dismission, Delia and Jabez’s connection to the Prattsburgh Congregationalists appears to have been nominal. They remained in the area, foregoing the act of physically moving to Prattsburgh. They appear in an 1850 Waterloo census record taken by Isaac Fuller. “Delilah,” 52, lives with Jabez, 54, a carpenter.

The 1862 Brigham’s Directory situates the Mathewses’ home in Waterloo at “20 Center” Street, 3.8 miles away from the Wesleyan Chapel (35).

Delia’s 1850 whereabouts in Waterloo make her involvement in the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 more logistically plausible. And Stanton singles out Reverend Bogue in her 1898 autobiography, 80 Years and More, for his hostile reaction to the conventions in Seneca Falls and Rochester. "The pastor of the Presbyterian Church, Mr. Bogue, preached several sermons on Woman's Sphere, criticizing the action of the conventions in Seneca Falls and Rochester," she writes (152). Stanton and Elizabeth McClintock (#16) published rebuttals in local papers, but Bogue had clearly not softened in his opposition and remained an adversary by the close of the decade.

In 1852, Delia and Jabez were, once again, part of a group that attempted to consolidate a Congregationalist church locally. This time, approximately 40 congregants hired on a pastor who had “served the Wesleyan Church on anti-slavery grounds for three years” (History 114). The pastor’s abolitionist orientation marks the church’s establishment, once again, in direct connection to the crisis of slavery, as opposed to matters of structure or theology. Yet again, the church was hobbled by the poor health of its pastor, and, by the time of its disbanding, former congregants were reabsorbed into the Wesleyan Chapel. The History of Seneca County pauses to reflect upon the dogged, decades-long commitment of these Congregationalists to build a church that met their spiritual and political expectations: “The germ of the first organization never died out, but retained its vitality during all the years of the suspension. They served with any branch of God’s people where in their judgment they could be the truest to their principles of civil and religious liberty. It is an interesting fact that three of the most honored of the present organization, viz., Mr. and Mrs. Jabez Mathews, and Abram Failing, Esq., were members of the organization of 1834” (114). Having fought to overcome these obstacles, time had nevertheless caught up with these brave souls. The History notes in 1876, “the years have whitened their locks and furrowed their brows, and ripened them for the ‘better land,’ where soon they will rejoin their old companions” (114).

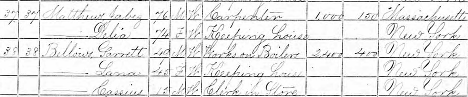

In the 1860 census, the Mathewses, 65 and 63, reside in Waterloo, and their wealth is assessed at 700 dollars:

By 1869, another aspiring Congregationalist enclave, which included Delia and Jabez, broke off from the Wesleyan Methodists. This effort was lead by church deacons Abram Failing and William Conklin, the father of signers Elizabeth Conklin (#30) and Mary Conklin (#32). This formation remained intact by the 1876 publication of The History of Seneca County.

By 1870, Jabez, 76 and Delia, 74, have returned to Seneca Falls, living next to the household of one Garret Bellows, who could possibly be a relative of Delia’s:

Their wealth is assessed at $1,150 by this time. I could find no evidence suggesting that Delia and Jabez had any children during their 64-year union.

The local directory of 1874 places their home at “Ovid n. Barker,” on the south side of the village (77). By 1879, Alonzo P. Lamey’s Auburn, Seneca Falls and Waterloo Directory notes that Jabez is now “retired” and resides on “Ovid n. Chapin” in Seneca Falls (277). These different designations likely represent the same location since Barker runs west of Ovid and Chapin runs east, both within a one-block distance of each other.

The New York State Death Index records Delia’s passing as occurring in Seneca Falls on January 20, 1883, age 85. Jabez died prior to her, on December 27, 1881, at 86 years old. Even with the information about Delia’s parents’ burial location, I failed to find any leads on the Mathewses’ place of interment. Hopefully, this will be revealed by future searches.

The Bement Affair was a polarizing, watershed event that, in many ways, set the stage locally for the Seneca Falls Convention. It reveals that the ecclesiastical groundswell of the Second Great Awakening dealt as much with contemporary politics as it did with religion. It spoke, in equal parts, to the individual's tenets surrounding the issues of slavery and the role women could justifiably take in opposition to it. Signer #14 broke the taboo and lent her voice to defend an ally within the church. She then weathered the repercussions that came with those actions. The disaffection that she likely felt as a result of the conflict of 1843 made her participation in the Seneca Falls Convention an inevitability.

Works Cited

Altschuler, Glenn C., and Jan M. Saltzgaber. Revivalism, Social Conscience, and Community in the Burned-over District: The Trial of Rhoda Bement. Cornell University Press, 1983.

"Delia Mathews." New York State Death Index, 1883. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Deliverance Bellows.” Findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/ memorial /48369204/deliverance-bellows. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

Evans, William & Wesley Crofoot. Seneca Falls & Waterloo Village Directory, 1874-5. Truair, Smith & Co.

Gray, Joan S., and Joyce C. Tucker. Presbyterian Polity for Church Officers. Westminster John Knox Press, 1998.

History of Seneca Co., New York. Everts, Ensign & Everts, 1876.

“Jabez Mathews-Delia Bellows Marriage.” U.S. and International Marriage Records, 1560-1900. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Jabez Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1840. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020. “

Jabez Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Jabez Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Waterloo, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Jabez Mathews Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Jabez Mathews-War Declaration.” New York, War of 1812 Certificates and Applications of Claim and Related Records, 1858-1869. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Jabez Mathews Pension Application.” War of 1812 Pension Application Files Index, 1812-1815. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

"Jabez Mathews." New York State Death Index, 1881. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

Jordan, John Woolf. Genealogical and Personal History of Northern Pennsylvania. Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1913.

Kling, David W. “Presbyterians and Congregationalists in North America.” Oxford University Press,https://oxford.university pressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780199683710.001.0001/oso-9780199683710-chapter-8. Accessed 26 Dec. 2020.

Lamey, Alonzo P. The Auburn, Seneca Falls and Waterloo Directory, 1879-80. Moses’ Publishing House, 1879.

Peck, Thomas Bellows. The Bellows Genealogy, Or, John Bellows, the Boy Emigrant of 1635 and His Descendants. Higginson Book Company, 1898.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Eighty Years and More. European Publishing Company, 1897.

“Thomas Bellows.” Findagrave.com, findagrave.com/memorial/ 146547689/thomas-daniel-bellows. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

“Thomas Daniel Bellows.” Clyde Appleton Bellows, Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1968. Ancestry.com. Accessed 20 Dec. 2020.

United States Senate. Senate Documents: 14th Congress, 1st Session-48th Congress, 2nd Session and Special Session, vol. 5, no. 2. Government Printing Office, 1883.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.