Signer #30, Elizabeth Conklin: "A Lucky Hit"

Born: Circa 1812, Albany County, New York

Died: November 14, 1884, Seneca Falls, 4th Ward

Occupations: Farmer, “Keeping House”

Searching for Declaration signers who are female and unmarried by 1848 has presented a special challenge in this research blog. It's because this demographic of unwed women is the most likely to get married in the future, assume a husband’s surname, and move out of the area. Once this occurs, the individual becomes exponentially harder to locate in archival searches and link up with her former identity. Elizabeth Conklin, Signer #30, falls into this category. I only managed to find details about her life post-marriage through a stroke of luck, as her name surfaced in a family genealogy belonging to her spouse.

Of course, the practice of choosing to retain one’s surname after marriage would not be established until the decade after the Seneca Falls Convention. Suffragist Lucy Stone stayed Lucy Stone after her May 1855 nuptials to Henry Brown Blackwell. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a friend and correspondent of Emily Dickinson and later a captain in the 51st Massachusetts Infantry, presided over Stone’s and Blackwell’s wedding. And after Lucy Stone pioneered it, keeping one’s name after marriage would hardly become commonplace.

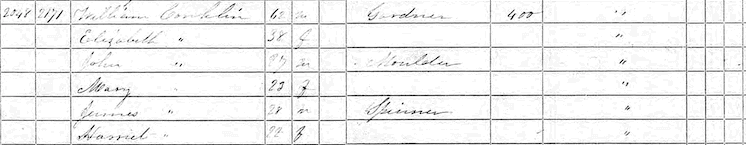

In an 1850 census record taken by Isaac Fuller, Elizabeth Conklin, 38 and a native of New York, appears in a Seneca Falls household. She lives with her father, William Conklin, 62 and a gardener, and her sister Mary Conklin (Signer #32), then 23 years of age. Siblings John, 27 and moulder by trade; James, 28 and a spinner; and Harriet, 22, reside in the same home. On the same page of the census, there is listed the household of Ansel Bascom, Seneca Falls mayor, a prominent reformer, Convention attendee, and state assemblyman. The same page also contains the household of Seabury S. Gould, the founder of Gould Manufacturing Co., the first pumpmaking business in Seneca Falls, and the patriarch of the local Gould family dynasty. Bascom’s wealth is estimated at $18,000, Gould’s at $2,000. Because of these proximities, it stands to reason that William Conklin made his living as gardener and groundskeeper by catering to the town’s first generation of wealthy entrepreneurs.

I did find some clues regarding the identity of the Conklin children’s mother and William’s spouse. One Mary Conklin is interred in the Ovid Street Cemetery in Seneca Falls. According to the ‘Grips’ Historical Souvenir of Seneca Falls, she passed away in 1846 at age 58 (38). This individual would have been the same age as William Conklin in 1846 and might have been the namesake of Mary Conklin (#32)—both moderate indicators that she might be a match. If this Mary Conklin was the mother of Signers #30 and #32, her 1846 death would have been an event of recent memory by the time of the Convention.

The village directories of 1862 and 1874 later situate the Conklin household in the 4th Ward of Seneca Falls (the southeastern quadrant) at “20 Garden” and “Garden cor. Spring,” respectively (41, 39). The 1852 illustrated map of the village confirms this, marking the home of William Conklin at the southeast corner of the intersection.

The W. Conklin Household in 1852 William’s record of activism makes it evident that political engagement was not a luxury reserved for Seneca Falls' affluent class. He was an open Free Soil Movement advocate (Wellman 206, 208). He would also assume a leading role in the group exodus from the local Methodist Church. The 1876 History of Seneca County records that, in the fall of 1869, “a large majority of the members of the Wesleyan Church, together with its pastor” took part in “seceding” and “proceeded to form themselves into a new society, to be known as the ‘First Congregational Church at Seneca Falls’” (114). Of the 63 individuals who disaffiliated from the Wesleyan Chapel congregation, William Conklin is identified as one of the splinter church’s three founding deacons. How this mass departure might relate to the eventual sale of the Wesleyan Chapel and the relocation of its remaining congregation in 1871 poses an interesting question (Brown 72). William would continue to reside with daughter Mary and her husband, passing away in 1881 at the age of 98 (Jackson & Jackson 110). His obituary records that he was born in Columbia County, New York, migrated to Seneca Falls in 1843, and had six living children at the time of his death.

The W. Conklin Household in 1852 William’s record of activism makes it evident that political engagement was not a luxury reserved for Seneca Falls' affluent class. He was an open Free Soil Movement advocate (Wellman 206, 208). He would also assume a leading role in the group exodus from the local Methodist Church. The 1876 History of Seneca County records that, in the fall of 1869, “a large majority of the members of the Wesleyan Church, together with its pastor” took part in “seceding” and “proceeded to form themselves into a new society, to be known as the ‘First Congregational Church at Seneca Falls’” (114). Of the 63 individuals who disaffiliated from the Wesleyan Chapel congregation, William Conklin is identified as one of the splinter church’s three founding deacons. How this mass departure might relate to the eventual sale of the Wesleyan Chapel and the relocation of its remaining congregation in 1871 poses an interesting question (Brown 72). William would continue to reside with daughter Mary and her husband, passing away in 1881 at the age of 98 (Jackson & Jackson 110). His obituary records that he was born in Columbia County, New York, migrated to Seneca Falls in 1843, and had six living children at the time of his death.

Some time after 1851, Elizabeth Conklin would marry James Albert Easton, a native of Hanover, New Jersey. I chanced upon this information through database-searches that lead me to Leon Nichols’ 1906 Genung, Ganong, Ganung Genealogy: A History of the Descendants of Jean Guenon of Flushing, Long Island. This volume reveals that Signer #30 was the second of Easton’s three wives. Easton had married Nancy Genung, a distant cousin and native of New Jersey, in March 1835 (109). Nancy and James appear with daughter, “S. A.,” in the Seneca Falls 1850 census, but, sadly, Nancy Easton would pass away on December 27, 1851 (Nichols 109).

I could not locate a record of James and Elizabeth in the 1860 and 1880 censuses. They are recorded in the 1870 census—James is 59, his employment is listed as “Farmer,” his assets in real estate assessed at $12,000, and his personal estate set at $1,600. Elizabeth, now 50, is recorded “Keeping House.” While the Eastons do not receive listings in village directories in 1862, 1867, or 1874, the Easton homestead is included in an 1874 map of Seneca Falls, located on the outskirts of the 4th Ward. It is set on what is now known as the “Garden Street Extension,” not too distant from the Garden Street household of William and Mary.

The J.A. Easton Household in 1874 Aaron M. Easton, James’ father, was counted among the first wave of European settlers in the area (Nichols 108, History 107). Still alive by the printing of the 1876 History of Seneca County, the author marvels over Aaron’s longevity: “There is at present living near Magee’s Corners, in the town of Tyre, a venerable man named Aaron Easton, who, born at Morristown, New Jersey, on February 6, 1775, and moving hither many years ago, has reached the age of full one hundred and one years. What but the excellent climate and the invigorating life of the farmer protracted his life beyond the common lot” (25).

The J.A. Easton Household in 1874 Aaron M. Easton, James’ father, was counted among the first wave of European settlers in the area (Nichols 108, History 107). Still alive by the printing of the 1876 History of Seneca County, the author marvels over Aaron’s longevity: “There is at present living near Magee’s Corners, in the town of Tyre, a venerable man named Aaron Easton, who, born at Morristown, New Jersey, on February 6, 1775, and moving hither many years ago, has reached the age of full one hundred and one years. What but the excellent climate and the invigorating life of the farmer protracted his life beyond the common lot” (25).

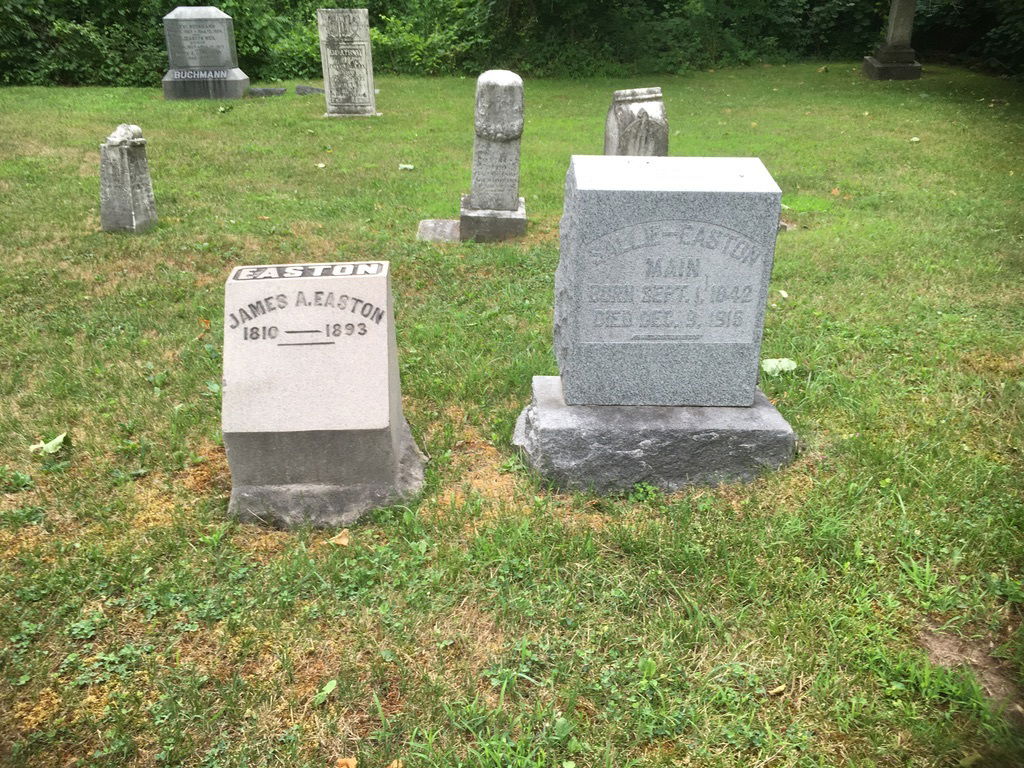

I could find little information regarding Elizabeth Conklin's life after 1870. According to the New York Death Index, Elizabeth Conklin passed away on November 14, 1884, age 72. The New York Marriage Index reports that James Easton, twice widowed and 76 years old at the time, would marry a third time, to one Sallie Pontius, age 45, in Geneva on January 4, 1887. According to church records, James Easton had been a member of the Presbyterian Church since 1831, and Sallie would join the church in 1892. James Easton passed away on May 7, 1893, in his eighty-second year. According to findagrave.com, he lies buried at Burgh Cemetery in nearby Fayette next to his third wife. I could not find a headstone for Elizabeth Conklin's gravesite at the site.

James Easton’s property was the subject of legal proceedings after his death. Beginning in March 1903, The Seneca County Courier-Journal would notify readers that a distributor, Sallie Main (James’ remarried widow), would parcel out the remainder of his valuable 4th Ward acreage under the supervision of the Waterloo Surrogate’s Office (7). Sallie Easton Main lies in rest next to James at Burgh Cemetery in Fayette; her death is dated on December 9, 1915.

Unable to find a written memorial or gravesite for Elizabeth Conklin, I had very little success tracking down details of Signer #30’s life after marriage. Often such archival traces (or lack thereof) correlate to an economic reality: it costs money to purchase an obituary or a headstone. It seems that many signers, members of the middle class in their day, fit into this category and suffer from this condition of archival absence. The paucity of details regarding these individuals suggests that the Seneca Falls Convention was the start of a grassroots movement, which attempted to draw in stakeholders from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds and walks of life. This included two unmarried daughters of a local landscaper.

Save for a brief entry regarding her death, the 1870 census, and a fleeting mention in her husband’s family genealogy, Elizabeth Conklin virtually disappears from archival records after marrying James Easton—even though she moved only a few blocks away.

Works Cited

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Brown, Sharon A. Historic Structure Report: Historical Data Section, Wesleyan Chapel, Women’s Rights National Historical Park, New York. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987.

Child, Hamilton. Gazetteer and Business Directory for Seneca County for 1867-8. 1867.

"Elizabeth Easton." New York State Death Index, 1884. Ancestry.com. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Evans, William & Wesley Crofoot. Seneca Falls & Waterloo Village Directory, 1874-5. Truair, Smith & Co.

History of Seneca Co., New York. Everts, Ensign & Everts, 1876.

“J.A. Easton.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2020.

“James Easton.” Presbyterian Church Records, 1701-1907. Ancestry.com. Accessed 5 May 2020.

“James Easton.” New York State Marriage Index, 1887. Ancestry.com. Accessed 5 May 2020.

"James Easton." Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104361234/james-a-easton. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Jackson, Mary Smith, and Edward F. Jackson. Marriage and Death Notices from Seneca County, New York Newspapers, 1817-1885. Heritage Books, 1997.

Nichols, Leon Nelson. Genung, Ganong, Ganung Genealogy: A History of the Descendants of Jean Guenon of Flushing, Long Island. A.W. Heinrich’s Printing Company, 1906.

"Sallie Easton Main." Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104502016/sallie-main. Accessed 5 May 2020.

“Seneca Falls Village in 1852.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 9 May 2020.

“Seneca Falls Village in 1874.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 9 May 2020.

“Surrogate’s Court.” The Seneca County Courier-Journal. 19 Mar. 1903, p. 7.

Welch, Edgar Luderne. ‘Grips’ Historical Souvenir of Seneca Falls, N.Y. Grip, 1904.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“William Conklin.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, Seneca County, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2020.