Signer #33: Susan Quinn, "The Teenager"

Signer #33: Susan M. Quinn Clark

Born: January 1834, New York State

Died: December 5, 1909, Seneca Falls, Age 74

Occupation: “Keeping house”

Local Residence: 24 Garden Street, Seneca Falls

Scotch-Irish surnames are distinctly underrepresented in the Declaration of Sentiments—with the notable exceptions of the signers from the M’Clintock and Conklin families as well as Signer #33, Susan Quinn. Quinn happens to be the youngest known signer, a teenager of about fourteen and a half at the time of the Seneca Falls Convention.

The scarcity of Irish-sounding names in the Declaration does not mean that there weren't any Irish-Americans living in the Finger Lakes Region in the 1840s. To the contrary, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, in her memoir Eighty Years and More (1848), recalls an “Irish settlement” located somewhere in the environs of Seneca Falls. Stanton fashions herself as a regulator and peace-keeper of sorts in this unruly place: “If a drunk husband was pounding his wife, the children would run for me. Hastening to the scene of action, I would take Patrick by the collar, and, much to his surprise and shame, make him sit down and promise to behave himself” (146). The Great Famine, lasting from 1845 to 1852, had created a wave of emigration from Ireland, with refugees destined for the United States and elsewhere. A multitude of New York households from this period consequently include individuals born in Ireland, typically female, hired on in the capacity of servants. Why did these individuals not take a more active role in the Seneca Falls Convention?

One contributing factor might involve the anti-Irish racism then prevalent in the United States. An inheritance of Great Britain’s colonization of Ireland, the racist figuration of the whisky-guzzling, hooliganist “Irish Ape” flourished during this period. Placards outside of businesses stating that “Help Wanted: No Irish Need Apply” were fixtures of American cultural life (Lind). Such artifacts are reminders that racism need not essentially pertain to skin color. It may instead be more accurately understood as a tool of colony and empire, deployed initially to dehumanize and exploit the labor of its victims.

Not above the sins of her day, Stanton engaged Irish stereotypes in her address at the Seneca Falls Convention. She complains of “the ignorant Irishman in the ditch”—he is in his ditch presumably because he is blind drunk. This rowdy, for Stanton, enjoys “all the civil rights” and privileges that a native-born, white American man is afforded by law, while women must endure without.

The daughter of an Irish immigrant, one wonders if Susan Quinn was present when Stanton spoke these words and how they must have affected her. Quinn would eventually marry and become a mother, spending her entire life in Seneca Falls. Unlike any other signer profiled so far, I was able to uncover specific details surrounding the cause and circumstances of her death.

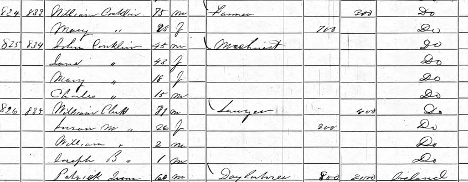

As with many signers, the first archival indication of Susan Quinn’s presence in Seneca Falls is the Declaration of Sentiments itself. After this, the 1850 census includes her in the household of her father, Patrick Quinn. Patrick is 57 and a day-laborer, born in Ireland. Susan’s mother, Mary Quinn, is 57 and a native of England. Susan is 16 in this census (so, 14 years old in 1848) with her birthplace given as New York. Later censuses date her birth to January 1834.

In Manual of the Churches of Seneca County (1896), Patrick Quinn is named as one of the founding members of the first Catholic church in Seneca Falls. It officially opened its doors in April 1836, placing his arrival in the area some time prior to this event (139). The Manual also notes that local parishioners did face backlash for trying to establish a place of worship: “There was much opposition encountered from the bigotry of prejudiced non-Catholics and the young church was persecuted” (139). Judith Wellman reports that Patrick Quinn eventually left the church in 1842 to become an Episcopalian, likely bringing Mary and Susan along with him (206).

The following year, Quinn acquired a residence located at 24 Garden Street in Seneca Falls (Wellman n242). The Garden Street home of “P. Quinn” is marked in the 1852 map of Seneca Falls, suggesting that he enjoyed some economic success and notoriety within the community by this time.

The Quinns live next door to the Conklin household, which includes signers Elizabeth Conklin (#30) and Mary Conklin (#32), whose names closely precede that of Susan Quinn in the Declaration. This sequence provides further evidence that neighborly ties drove involvement in the Convention. It also suggests that such bonds influenced the order in which signatures are laid down in the document, regardless of any intention to this effect on the part of the signers themselves.

The Quinns live next door to the Conklin household, which includes signers Elizabeth Conklin (#30) and Mary Conklin (#32), whose names closely precede that of Susan Quinn in the Declaration. This sequence provides further evidence that neighborly ties drove involvement in the Convention. It also suggests that such bonds influenced the order in which signatures are laid down in the document, regardless of any intention to this effect on the part of the signers themselves.

Some time in the first half of the 1850s, Susan married William Clark, a lawyer 14 years her senior. According to Judith Wellman, Susan had two twins in 1855, both of whom died in infancy (223). By 1860, newlyweds Susan and William live with Patrick at the house on 24 Garden Street. They have two toddlers now: William, 2, and Joseph, 1. Mary Conklin and her father, William, still live next door.

Patrick has accumulated some wealth by 1860: his assets are valued at $2800 in this census. Susan’s mother, Mary, does not appear in this or any subsequent censuses.

A short description of William Clark’s life and career is given in Hamilton Child's Seneca County directory for 1894. He was born in in Charlton, Saratoga County, in 1819. William made his living as a justice of the peace, who “was formerly master in chancery until that office was abolished” (268-9). A master in chancery was essentially a legal jack-of-all trades, who assisted the court in clerical duties and could receive sworn testimony (269). Clark is elsewhere identified as a “police justice,” which signifies that he could preside over the litigation of minor criminal offenses (587). The county directories produced in 1862 and 1867 place his offices at 59 and 61 Fall Street, respectively (78, 129).

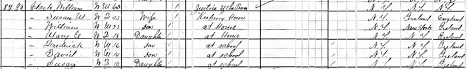

The family has added 4 more children by 1870. Susan is 36 and “Keeping house.” A "Justice of Peace," William is 50. Willie, Joseph, Mary, Frederick, David, and Susan Jr. range in age from 12 years to 9 months. Elisa Brown, 29, is a domestic servant hailing from Ireland. Mary and William Conklin still live next door.

Susan’s father, Patrick, is absent from this census. Patrick is listed in the 1862 county directory but is absent from the 1867 directory, giving a possible window of time for his passing (62).

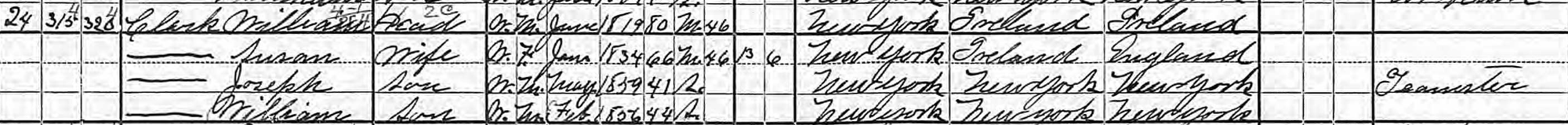

By 1880, William, now 60, is listed as a “Justice of the Peace” and Susan, 45, is “Keeping House.” Ranging in age from 22 to 10, William, Mary, Frederick, David, and Susan are “at Home” or “at school.”

By 1900, Joseph and William, 41 and 44, reside with Susan, 66, and William, 80. At this point, the Clarks have been married for 46 years. The 1900 census contained the rather intrusive questions of how many children a woman had given birth to versus the number of children who survived up to the present. Susan responded that she had given birth to 13 children, of which 6 were still living.

The New York State Death Index reports the passing of a William Clark, a resident of Seneca Falls, in April 1903. In the 1905 state census, Susan, now 71, is listed as head of household. She resides with sons William and Joseph, and the latter now works as a police officer.

Susan Quinn Clark passed away on Sunday, December 5, 1909. The sad circumstances of her death were published in The Seneca County Courier-Journal and elsewhere. Up to the time of her passing, Susan had become “an invalid and had been confined to her room for the past three years.” To keep warm in early December, she was in the process of lighting scraps of newspaper in order to feed a small fire. The flames caught Susan's clothing. “Her son, Joseph,” it continues, “who was in the house, heard her cries and extinguished the flames but not until she had been severely burned, the injuries and shock causing her death.” The newspaper notes that she is survived by three sons, Joseph, David, and Fred, who reside in Seneca Falls. Daughters Mrs. Susan Bachman and Miss Mary E. Clark, who both live near Waterloo, also survive her. Susan Quinn, Signer #33, is interred in Restvale Cemetery (“Susan Q. Clark”).

By 1920, Susan's son Joseph still resides on Garden Street, meaning that members of the Quinn family had lived on the same piece of property for nearly 77 years by this point. Fred Clark is listed in 1920 as a church caretaker who boards in a household in the second ward of Seneca Falls. Susan Bachman and Mary Clark, Susan Quinn’s daughters, live together in the first ward of the village. Mary works as a cook, and Susan Bachman’s daughter Eola is employed as a teacher.

Judith Wellman and others record that Millicent Brady Moore, a great-granddaughter of Susan Quinn through her son David, ran the first leg of a torch relay celebrating the United Nations’ decade of women in 1977 (237). Moore passed away in 2011 at the age of 92, a lifelong resident of Seneca Falls ("Millicent Moore").

Did anti-Irish prejudice manifest a set of exclusionary tactics at the Convention? If so, what exempted an American of Irish extraction, like Susan Quinn, from them? Or, perhaps, the radical politics being espoused in the Declaration of Sentiments was unappealing to local Irish Catholics and preempted their involvement. The specter of racism would dog the Suffrage Movement for much of its existence after 1848, dampening the more-inclusive collective impact it could have had. In the case of Signer #33, the racism faced by Irish Americans—which is plainly articulated by Stanton at the Convention—did not deter the teenager from signing her name to the roll.

Works Cited

Brigham, DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Child, Hamilton. Gazetteer and Business Directory for Seneca County for 1867-8. 1867.

---. Reference Business Directory of Seneca County, N.Y., 1894-95. E.M. Child, 1894.

“Death Results from Burns.” Seneca County Courier-Journal, 9 Dec. 1909, p. 1.

“Frederick Clark Household.” Federal Census, 1920. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

"Joseph Clark Household.” Federal Census, 1920. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Lind, Dara. “Why Historians Are Fighting about ‘No Irish Need Apply’ Signs — and Why It Matters.” Vox, 17 Mar. 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/3/17/8227175/st-patricks-irish-immigrant-history. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Manual of the Churches of Seneca County with Sketches of Their Pastors, 1895-96. Courier, 1896.

“Millicent Moore Obituary.” Finger Lakes Times, https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/fltimes/obituary.aspx?n=millicent-moore-brady&pid=147977933&fhid=10767. Accessed 10 May 2021.

“Patrick Quinn Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

“Seneca Falls Village in 1852.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. “Address of Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Delivered at Seneca Falls & Rochester, N.Y., July 19th & August 2nd, 1848.” Robert J. Johnston, 1870.

---. Eighty Years and More. European Publishing Company, 1897.

“Susan Bachman Household.” Federal Census, 1920. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

“Susan Clark Household.” New York State Census, 1905. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

"Susan Quinn Clark". Findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave. com/ memorial/170878015/susan-m.-clark. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“William Clark Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

“William Clark Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

“William Clark Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

“William Clark Household.” Federal Census, 1900. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.

"William Clark." New York State Death Index, 1903. Ancestry.com. Accessed 10 May 2021.