Signer #91: S.E. Woodworth, "Drosophila"

Signer #91: Stephen Elias Woodworth

Born: November 27, 1814, Tyre, Seneca County

Died: June 23, 1887, Champaign, Illinois, Age 72

Occupations: Merchant, Grocer, Tailor

Local Residence(s): Seneca Falls & Tyre, Seneca County; Montezuma, Cayuga County

Special thanks to Hanns Kuttner and Amy Lavelle for research assistance provided for this profile.

One unique pattern that has emerged in the course of researching the 100 signers involves the disproportionate amount they contributed to fields of science and medicine. In experiments conducted in Seneca Falls, Eunice Newton Foote (Signer #5) first discovered the link between atmospheric carbon dioxide and climate change. Lucretia Mott (#1), Charlotte Woodward (#37), and E.W. Capron (#97) each had special ties to the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, one of the first institutions worldwide to award women the M.D. degree.

The pattern also holds true if extended to signers’ immediate family members. To this point, a close relation of Signer #91 was responsible for one of the great leaps forward in 20th century science. Charles Woodworth, signer Stephen E. Woodworth’s nephew and stepson, pioneered the technique of breeding the common fruit fly as a model organism for scientific investigation. An entomologist by training, Charles first realized that the bug, from the genus drosophila ("dew loving"), was ideal for experimentation because of its conveniently brief reproductive cycle and its ability to thrive in tight spaces with minimal resources. After all, it can subsist on nothing more than a little bit of rotten fruit. Drosophila can also be readily observed with the naked eye or under low magnification, and it poses no danger in instances of lab leak (Markow). If mutant fruit flies were to escape from a research facility, they would not be a threat to public health.

Charles Woodworth shared his “discovery” of the fruit fly with colleagues, who eventually relayed the technique on to Robert Hunt Morgan. Beginning in 1909, Morgan used drosophila to study hereditary mutations among fruit fly generations. Through this research, he validated the theory that chromosomes carry genetic information, which is passed down and expressed in offspring. Charles Woodworth’s utilization of the fruit fly would consequently help to hypercharge the study of biology in the 20th century. While the chromosomal make-up of drosophila is relatively simple compared to that of humans, it still bears a number of key analogues to human genetics, making it ideal for the study of inherited diseases (Markow). Morgan won the Nobel Prize in 1933, and his profile on Nobel’s website credits Charles for first recognizing the eminent value of the harmless, little fruit fly (“Robert Morgan”). In addition to this, Charles Woodworth had four species of insect named in his honor, and he made important contributions to the fight against mosquito-borne malaria (Holden 148, 161, 165).

The fact that Signer #91 was Charles Woodworth’s uncle and stepfather is a prime illustration of how familial and social bonds endured amidst the geographical dislocations and mortality of Manifest Destiny. S.E. Woodworth’s westward peregrinations after the Seneca Falls Convention would be at the center of a Supreme Court case, which, it is speculated, helped to pay for Charles Woodworth’s college education. My research into Signer #91 was aided by a 2015 biography of Charles Woodworth authored by Brian Holden, a direct descendant. Family trees constructed by users on Ancestry.com were also very useful in creating this profile.

Stephen Elias Woodworth was born in Tyre on November 27, 1814 (Behan 329). According to the 1876 History of Seneca County, Stephen’s grandfather Caleb Woodworth initially migrated to Tyre in 1805 and established a farm of 400 acres in the hamlet (124). Stephen’s parents, Caleb Woodworth II and Betsey Crawn/Crane, were married in Tyre in 1807, only the second marriage among the settler community there (125). S.E. was the fourth of 12 children from his father’s three marriages (Behan 328-9).

As an adult, Stephen married Rachel Bell in 1840, and the couple had a son, Thomas, in October 1841 (“Thomas Woodworth,” “Fred Woodworth”). Rachel passed away in July 1845, and she lies buried in Mentz Church Cemetery in Montezuma, Cayuga County (“Rachel Woodworth”). It is not clear exactly when the Woodworths moved from Tyre to Seneca Falls, but, by the 1840s, Signer #91 had started a general store in the village with the help of his brother Alvin Oakley Woodworth.

Located at the corner of Ovid and Bayard Streets, the spot occupied by the Woodworths’ retail operation would become known locally as “the Woodworth block” and is only a short distance from the Wesleyan Chapel. The outfit catered, it seemed, to all the needs and whims a Seneca Falls consumer could have. A 1907 article by B.F. Beach in The Seneca County Courier-Journal imparts a nostalgic sense of the shop’s wide variety. Quoting an 1847 newspaper advertisement, it states: “Stephen E. Woodworth says he is at home in the Woodworth block, and offers at wholesale and retail dry goods, groceries, carpetings, boots and shoes, hats and caps, books and stationery, wall and window paper, stone and wooden ware, muffs and furs, and ready-made clothing of his own manufacture and warranted well made. No trouble to show goods—himself and four clerks ready to wait on you.” Judith Wellman records that Stephen and Alvin also advertised candy and toys, and they even boasted that their business was the “’cheapest bookstore in the United States’” (6).

The 1852 map of Seneca Falls includes the Woodworth store—perhaps even indicating that it also functioned as hotel.

Their reach perhaps exceeding their grasp, the Woodworth brothers’ attempt at one-stop shopping was met with a number of financial difficulties. Signer #91 was forced to declare bankruptcy at least four times in the 1840s and 50s (Wellman 6, 223).

On the bright side, Stephen appears to have met his second wife through business connections. In 1913, Janet McKay Cowing recalled that one Ruth Gilbert started a hat-making venture in 1836 that operated out of the Woodworth block until 1841, selling “’shaker hoods, silk and lawn bonnets, flats for young people, etc.’” (Cowing 53). In 1848, Ruth Gilbert brought two sisters, Ann and Mary, into the enterprise, the latter being a strong candidate for Signer #23 (53). Some time around 1848, hatmaker Ann E. Gilbert married Stephen Woodworth and “continued the millinery business in her husband’s store” (53).

During this period, Stephen was politically affiliated with the Free Soil Party, like many male Declaration signers (Wellman 208). At the Seneca Falls Convention, he took an earnest interest in the topics at hand. The 1848 John Dick report on the Convention singles him out as one of the individuals who “freely discussed” the Declaration after its recitation by Stanton (6). Stephen was a Baptist, one of the lesser-represented Protestant denominations at the Convention, a feature he shares only with Signer #75, Henry Seymour (Wellman 206). He is also the fourth male signer profiled so far whose spouse did not sign the Declaration, despite her having the means and opportunity to do so.

Woodworth descendant Brian Holden remarks that his family had no knowledge or memory of their ancestor’s involvement in the Convention (32). Such an absence seems to be a standard phenomenon that squares with contemporary events in 1848. Declaration signers and Convention participants, it is said, were hesitant to publicize their involvement for fear of the negative repercussions it might generate. Operating as something akin to a taboo, they probably also neglected to pass on details of their experiences to members of the younger generation, creating an intergenerational lack of awareness among descendants.

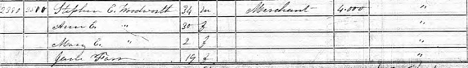

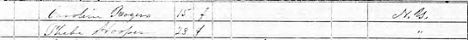

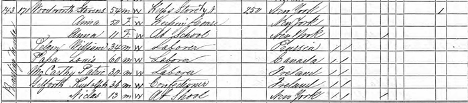

An 1850 Seneca Falls census record taken by Isaac Fuller includes Ann, 30, and Stephen, 34, a merchant. They have a daughter Mary, 2, likely named in honor of Ann’s sister. Their net worth is assessed at $4,000.

Two teenage females and one young adult female reside in the same household, most likely as boarders or domestics. The Woodworths appear on the same census page as Abram Failing, a leader of the local Congregationalist community and abolitionist. Failing’s home address by 1862 is 77 West Bayard, a possible location for the Woodworths’ residence in 1850 (Brigham 45).

Whatever condition the Woodworth brothers’ general store was in by the turn of the decade, it was dealt a blow by Alvin’s departure for the West. Beach reports that Alvin “was connected" with Stephen in business "for a while, then he got the Western fever and went to the Pacific coast. He had so much to say about that country that he was designated as ‘All Out West’ Woodworth,” a nickname that plays on Alvin’s initials.

I could not find any record regarding Alvin actually reaching the Pacific territories. He married Cynthia Ward, a New York native, in 1851. She died in Illinois in March 1857, possibly as a result of childbirth (“Cynthia Woodworth”). He returned to the Finger Lakes Region the following July to remarry. An 1857 newspaper notice announces that Alvin, now a resident of Urbana, Illinois, has wedded Sarah Mandeville in her hometown of Canoga, Seneca County (Jackson & Jackson 35). Sarah subsequently died in Illinois in June 1860, aged 22. Twice widowed, Alvin was married a third time in 1861 to Mary Carpenter, a native of Manlius, New York. Alvin then died himself in Illinois on February 4, 1869 (“Alvin Woodworth”).

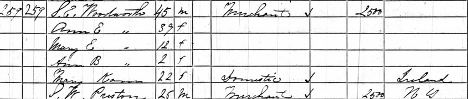

Back in the Finger Lakes Region, Stephen and Ann have moved to Montezuma by the time of 1860 census. Mary is now 12 and a baby daughter, Ann Bell, is 2. An Irish-born domestic and a merchant board with them. The Woodworths’ assets are estimated at $2,500, a sharp decline from the previous decade.

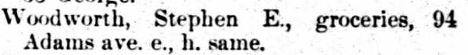

At some time in the 1860s, Signer #91 followed his brother’s lead and went out West. As was the case for Henry W. Seymour (#74), Stephen’s business and financial troubles in Seneca Falls could only have made the prospect of emigration more attractive. By the end of the decade, Ann and Stephen surface in Detroit, Michigan. An 1869 city directory shows them operating a grocery on Adams Avenue, where they also reside (414).

They are present in the 1870 census for Detroit:

Daughter Ann B. is now 11 and at school; both in their 50s, Stephen “Keeps Store,” and Ann is recorded as “Keeping House.” The vertical script in the lefthand column indicates that their home also operates as a boarding house, with customers hailing from Prussia, Canada, and Ireland. The Woodworths’ wealth is now valued at $250. This amount represents a considerable reduction from their standing in New York and captures the financial strains of moving west during this era.

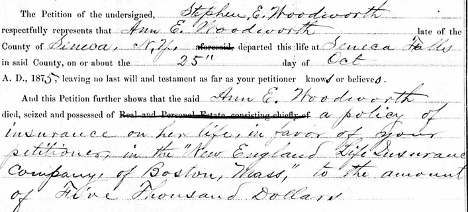

Stephen’s spouse Ann died on October 21, 1875, in Seneca Falls. The fallout from her passing would incite the legal dispute that Stephen would spend much of the rest of his life litigating. In September 1869, a life insurance policy was purchased on Ann’s behalf from an agent of the New England Life Insurance Company, headquartered in Boston (“Law Department”). It is not known why Ann had left Michigan to undertake the considerable journey back to New York, and it is unclear whether she was simply visiting or had returned permanently.

In the aftermath of his second wife's death, Stephen Woodworth promptly left Michigan for Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. On September 5, 1876, he married his brother's widow, Mary (Holden 23). Born in 1842, she was 28 years younger than her newlywed husband, and she had not remarried since Alvin’s death seven years earlier. In his haste to move to Illinois and wed, Stephen had not fully settled his late wife’s affairs in Michigan.

The following January, Stephen filed a probate letter identifying himself as both the administrator of Ann’s estate as well as the beneficiary of her $5,000 life insurance policy. Otherwise, she left behind no assets and died intestate.

New England Life initially refused to honor the claim on the grounds that regular payments had not been maintained by the policyholder. In February, Stephen sued his wife’s reluctant insurer in a Chicago court.

New England Life initially refused to honor the claim on the grounds that regular payments had not been maintained by the policyholder. In February, Stephen sued his wife’s reluctant insurer in a Chicago court.

The case was argued in civil court in the Southern District of Illinois during the summer of 1880. Before a jury of five, attorneys for New England Life said that the policy had lapsed because of “non-payment of premiums.” Lawyers for the plaintiff argued that “the company was negligent in notifying Woodworth of the non-payment” (“Court Record”). The jury ultimately decided in Stephen Woodworth’s favor, awarding him $5,348.73, which appears to equal the policy plus interest and/or legal fees.

New England Life took a different approach in its subsequent appeals, filing a “writ of error” that focused on the fact that Ann had never lived in Illinois, where the claim was now being made. Ann was a resident of Michigan where the policy was purchased, and her estate should be administered from the same place (“Law Department”). No precedent had been set in this matter, so the case slowly made its way through the legal system.

Seven years after the initial filing, the case arrived at U.S. Supreme Court. In March 1884, the high court reached a decision, finding for the plaintiff and determining that state borders were immaterial to a life insurance policy or to the administration of an estate. News of the decision was reported broadly at the time (“Supreme Court”). One might imagine how this legal precedent raised life insurance premiums and presented a dilemma for insurers. Now, policy holders could proceed to the West, to reside in frontier territories and states with much higher death rates than where the policy was first taken out. A husband could conceivably buy a policy for his wife then travel with her to the West, without needing her consent.

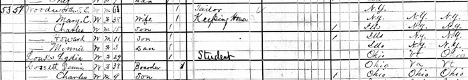

While waiting for the decision to come down, Stephen and Mary had two girls, Minnie, born in 1877, and Metta, born in 1880 (University of Illinois 221, 313). In the 1880 census for Champaign, Stephen is 63 and a tailor. Mary is 38 and “Keeping House.” Alvin’s biological son Howard is 11, and Charles, the future entomologist, is 15. Minnie is now 3.

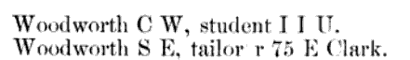

They have 3 boarders, including one female student, who probably attends nearby University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). An 1883 directory for Champaign places the Woodworth home at 75 East Clark Street.

Stephen is listed immediately after Charles, now a college student (86).

According to his headstone, S.E. Woodworth passed away on June 23, 1887. He is interred in Mount Hope Cemetery in Urbana alongside many members of his extended family (“Stephen Woodworth”).

Stephen’s widow, Mary resides in Champaign with Howard and Metta by the time of the 1900 census (“Mary Woodworth”). She would remarry a fourth time in 1904 and pass away in 1909 (“Mary Judy”).

Ann’s and Stephen's daughter Anna Bell Woodworth moved to Lansing, Michigan, and married in 1881 (“Anna Woodworth”). She died in March 1888, age 29 (“Anna Alexander”). Ann’s and Stephen’s daughter Mary also settled in Lansing. She works as a bookkeeper in the 1910 census and lives with her daughter (“Mary Christopher”).

Rachel’s and Stephen’s son, Thomas Bell Woodworth also migrated to Michigan. He would become a successful farmer and practice law. He resides for the 1870 census in Caseville, Huron County, with a wife, Mary, and two sons, all born in New York. He passed away in Caseville in 1904 (“Thomas Woodworth”).

According to a UIUC alumni directory from 1913, Stephen’s and Mary’s daughter Metta received a bachelor’s degree and briefly worked as a lecturer in health science at the Farmers’ Institute at the University of California. At the time of publication, she works as assistant postmaster in Lowell, Nebraska (313). Stephen's and Mary’s daughter Minnie received a bachelor’s degree from UIUC in 1899, married, and has settled in Kansas City by 1913 (221).

Alvin’s and Mary’s son Howard would study at Cornell and specialize in entomology, like his brother Charles. He would initially become a teacher but, by 1913, he works as a bookkeeper in Champaign. By 1913, Alvin’s and Mary’s son Charles Woodworth has landed at the University of California, Berkeley, and has started a family (132). The 1913 UIUC alumni directory makes no mention that he had, by that point, discovered the fruit fly.

Stephen E. Woodworth has one other notable family relation. His niece Grace Woodworth, the daughter of his brother Josiah, became a photographer and opened a studio in Seneca Falls. She is remembered for her portraits of Susan B. Anthony and pictures of the Seneca County landscape (Gable, Wellman 223, Barbieri & Jans-Duffy 61).

Signer #91 did not have long to enjoy the financial windfall from the Supreme Court’s decision, dying only three years after it was handed down. Brian Holden speculates that the proceeds from the civil trial helped to pay for Stephen’s children’s and stepchildren’s/nephews' education (50). Howard, Minnie, Metta, and Charles would all attend UIUC after Stephen’s death.

Each strange twist of fate in the life of Stephen Elias Woodworth begs the question of whether the fruit fly would have been discovered if Charles Woodworth had not gone to college, drawing on the proceeds of his dead aunt’s life insurance. Would drosophila still be an insignificant bug if Stephen and Ann had not migrated west to Michigan? Where would Robert Hunt Morgan’s crucial advancements in genetics then be without his experimentation with the fruit fly? The chain of events that lead to this invaluable development in science can be traced back to Seneca Falls and to Signer #91.

Works Cited

“Alvin Oakley Woodworth.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 29 July 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/226098789/alvin-oakley-woodworth.

“Ann E. Woodworth—Will” Illinois, Wills and Probate Records. Ancestry.com. Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Anna B. Alexander—Death.” Michigan State Death Index, 1888. Ancestry.com. Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Anna Woodworth—Frank Alexander Marriage.” Michigan Marriages, 1881. Ancestry.com. Accessed 28 July 2021.

Barbieri, Frances, and Kathy Jans-Duffy. Seneca Falls. Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Beach, B.F. “Early Merchants of Seneca Falls.” Seneca County Courier-Journal, 18 July 1907, p. 1.

Behan, Jeanette Woodworth. The Woodworth Family of America. J.W. Behan, 1988. Brigham,

DeLancey. Brigham’s Geneva, Seneca Falls, and Waterloo Directory and Business Advertiser, For 1862 and 1863. 1862.

Clark, Charles F. Detroit City Directory, 1869-70. 1869.

“The Court Record.” Daily Illinois State Journal, 2 July 1880, p. 3.

Cowing, Janet McKay. "Early Milliners of Seneca Falls." Papers Read Before the Seneca Falls Historical Society For the Years 1911-12. Seneca Falls Historical Society, 1913, pp. 53-7.

“Cynthia Woodworth.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 29 July 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/226114545/cynthia-e-woodworth

“Fred Woodworth—Sons of the American Revolution Application, 1928.” Michigan State Sons of the American Revolution. Ancestry.com, Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

Gable, Walt. “Looking Back: Susan B. Anthony was SF Photographer’s Most Famous Subject” Finger Lakes Times, Accessed 29 July 2021, https://www.fltimes.com/lifestyle/looking-back-susan-b-anthony-was-sf-photographers-most-famous-subject/article_d83c2e89-fe3a-538a-90c5-490728ce80fd.html.

History of Seneca Co., New York. Everts, Ensign & Everts, 1876.

Holden, Brian. Charles W. Woodworth: The Remarkable Life of U.C.’s First Entomologist. Brian Holden, 2015.

Jackson, Mary Smith, and Edward F. Jackson. Marriage and Death Notices from Seneca County, New York Newspapers, 1817-1885. Heritage Books, 1997.

Johnson’s Urbana-Champaign, Illinois City Directory. Johnson Publishing Company, 1883.

“Law Department.” The Baltimore Underwriter, 5 Sep. 1884, pp. 110-112.

Markow, Theresa. “The Secret Lives of Drosophila Flies.” NIH, Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4454838/

“Mary E. Christopher.” Federal Census, 1910. Lansing, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Mary Judy.” Findagrave.com. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/225879077/mary-celine-judy.

“Mary Woodworth.” Federal Census, 1900. Champaign, Illinois. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Rachel Bell Woodworth.” Findagrave.com. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/40072348/rachel-woodworth

Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, Held at Seneca Falls, N.Y., July 19th and 20th, 1848. John Dick, 1848.

“Seneca Falls Village in 1852.” Maps of Seneca County & Various Town – Seneca County, New York. Accessed 9 May 2020. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/maps-of-seneca-county-various-town/.

“Stephen E. Woodworth Household.” Federal Census, 1850. Seneca Falls, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Stephen E. Woodworth Household.” Federal Census, 1860. Montezuma, New York. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Stephen E. Woodworth Household.” Federal Census, 1870. Detroit, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Stephen E. Woodworth Household.” Federal Census, 1880. Champaign, Illinois. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Stephen Elias Woodworth.” Findagrave.com. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/226104584/stephen-elias-woodworth

“Supreme Court.” The Indianapolis Journal, 1 Apr. 1884, p. 4.

“Thomas B. Woodworth.” Federal Census, 1870. Caseville, Michigan. Ancestry.com, Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Thomas Bell Woodworth.” Findagrave.com, Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/127166631/thomas-bell-woodworth.

“Thomas H. Morgan Biographical.” The Nobel Prize, Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1933/morgan/biographical/

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. The Alumni Record of the University of Illinois at Urbana, 1913. University of Illinois, 1913.

U.S. Supreme Court. “New England Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Woodworth.” Justia.com, Accessed 29 July 2021. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/111/138/.

Wellman, Judith. The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the First Woman’s Rights Convention. University of Illinois Press, 2010.