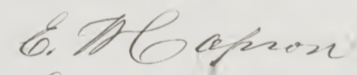

Signer #96, E.W. Capron: "The Wandering Spirit(ualist)"

Signer #96, Eliab Wilkinson Capron

(b. Finger Lakes Region, New York, Circa 1820--d. New York City, April 18, 1892)

“Now I am ready, my friends. There will be great changes in the nineteenth century. Things that now look dark and mysterious to you, will be laid before your sight. Mysteries are going to be revealed. The world will be enlightened. I sign my name Benjamin Franklin. Do not go into the other room.”

—Message from Benjamin Franklin, from Singular Revelations (1850), 94-5.

Thanks to Judith Wellman and Charles Lenhart for their assistance researching this profile.

On March 15, 1844, The Liberator reprinted an open letter from then twenty-four-year-old E.W. Capron. It carries a Walworth dateline and is addressed “To Farmington Monthly Meeting of Friends,” based out of Ontario County, New York, and announces that “after long, earnest, and careful deliberation…I can no longer, consistently, remain a member of your Society” (2). The author is disaffiliating from this community of Hicksite Quakers because of their passive stance, in his estimation, to the institution of slavery. “You are bowing down to the wicked and corrupt sentiment…which despises the negro on account of caste and not of color;—by lifting up your voice against those who are pleading for their deliverance;—by neglecting to act with others who are laboring peacefully to effect their emancipation.” He alleges that members of the Farmington Monthly Meeting have done too little to resist involvement, even tangential involvement, in the economic and political systems that abet the peculiar institution. Steps taken to prohibit or suppress discussion of the ills of “Slavery, War, Intemperance, Priestcraft and Sectarianism” at meetings have also prompted Capron’s departure.

So began a life of philosophical restlessness and seeking—often guided by spirits—for Eliab Wilkinson Capron, the ninety-sixth signer of the Declaration of Sentiments. Now for the all-important question: is his name spelled correctly in reproductions of the Declaration? In the 1889 first volume of The History of Woman Suffrage, 1893’s NAWSA Handbook, 1908’s “Roll of Honor,” and the Declaration reproduced on the front page of The Seneca County Courier-Journal in July 1923, there is not a single variation in the rendering of his name (809, 835). In John Dick's 1848 Report of the Women's Rights Convention, however, a typesetting error produces the name "E.W. apron," in keeping, oddly, with the transcriber's objectification of signer names explored in the profiles of Robert Smallbridge and Mary S. Mirror (11).

Placing this error aside, this uniformity suggests that E.W. Capron was a regionally known figure, plugged into the various activist networks gaining steam in the 1840s. As it turns out, Eliab Capron did not have too many irons in the fire of the Burned-Over District. He had all the irons in all the fires. And through his involvement in the lives of the Fox Sisters, Capron even played a pivotal role in fanning the flames of one of the period’s definitional movements, spiritualism. He spent much of his career multitasking as political commentator, local politician, and newspaper editor, engaging with many of the key reformers of the day and generating a massive archival footprint. In his profile, I also examine the remarkable lives of E.W. Capron’s wife, Rebecca M.C. Capron, and their daughter, Evalyn M.C. Harvey.

Born around 1820, Eliab was the eldest child of David Capron and Mary Knight. In Frederic Augustus Holden’s 1859 Genealogy of the Descendants of Banfield Capron, the author notes that, by 1859, David “died many years since, in Williamstown, N.Y.”—though this might be mistaken for Williamson, New York (182). According to Judith Wellman, Marjory Allen Perez, and Charles Lenhart, the death of Eliab’s father in the late 1830s compelled his widowed mother, Mary, to relocate the family to the Finger Lakes region and move around frequently during this period, to places like Scipio, Farmington, and Auburn (326).

Even before his very public departure from the Farmington Monthly Meeting, Capron had begun to partake in a dizzying amount of activist endeavors. In his twenties, he wrote vigorously on political matters, having letters-to-the-editor reprinted in (apart from The Liberator) The National Anti-Slavery Standard, The North Star, and The National Era (Wellman et al. 326, 331). Untethered to the local Hicksite community after his 1844 renunciation, he became a communard, joining the short-lived Fourierist phalanx at Sodus Bay, located on Lake Ontario. Here, Eliab married Rebecca May Cooper, born in Williamson on January 11, 1825 (“Rebecca Capron”). An index of New York marriages makes the aside that this ceremony was undertaken on June 12, 1844, “by themselves," suggesting that vows were exchanged without clergy or a justice of the peace (Bowman 39). The Caprons’ marriage without an officiant has roots in Quaker tradition, and it would also have squared, to a degree, with Charles Fourier’s disdain for what, he alleged, were the outmoded and oppressive strictures placed upon women through the barbaric tradition of marriage. The Sodus Bay community would be fully defunct by 1846, and the Caprons likely departed some time in 1845, living in Rochester and then settling in Auburn (Wellman et al. 331).

By the summer of 1848, Capron landed a job as editor of The Auburn National Reformer (Wellman et al. 332). The journey from downtown Auburn to the Wesleyan Chapel is approximately 15 to 16 miles on modern roads, making his trip to Seneca Falls the greatest distance traveled among the eight signers of the Declaration profiled up to this point. In the account of the Seneca Falls Convention included in the first volume of The History of Woman Suffrage, Capron is shortlisted (like fellow-editor Frederick Douglass, Signer #73) as one of a handful who “took part throughout in the discussions” (69). As the Declaration’s 96th signer, the proximity of Capron’s name to Signer #100, Azaliah Schooley, is telling. Schooley, a member of the Junius Monthly Meeting, had served on an investigatory committee of the Farmington Quarterly Meeting that ultimately recommended Capron’s 1844 expulsion be rescinded (Wellman et al. 329). The proximity between the signatures of Capron and Schooley might suggest that some residual sense of alliance still existed, in spite of Capron’s recent falling out. Schooley’s involvement in abolition would have been another enduring tie between the two.

While they might not have been aware of it at the time of the convention, another looming point of similarity between Schooley and Capron would emerge in the coming months and years. Both men would both come to share an affinity for spiritualism and séance, partially driven by their social contacts with Isaac and Amy Post (Signer #10). The Posts would, in fact, help to facilitate the introduction between Capron and the Fox Sisters—Leah, Margaretta (“Maggie”), and Catherine (“Cathie”) of Hydesville—the spirit media who would capture the attention of the nation and spark a spiritualist cultural upheaval (Underhill 28). The part that Capron played in the birth of spiritualism would not be a passive one. He would serve, at times, as the Foxes’ de facto manager, publicist, and apologist.

The Foxes’ origin story is well told. And their ties to Signer #96 reveal the foundational connections that would persist between Suffrage and spiritualism for decades to come. Starting in late March 1848, Cathie and Maggie claimed to have been contacted by a spirit entity, which manifested itself through the intermittent production of knocks and wraps in their Hydesville home. The sisters soon devised a method of communication with the spirit that involved question and response-via-knock. This method of communication revealed that the spirit, causing so much agitation, was the restless ghost of one Charles B. Rosna, a traveling peddler murdered by the home's previous tenants. Once the channel of contact had been opened with the ghost of Rosna, other spirits began flooding in with their own communiques, requests, and demands (“Hydesville Park History”).

It is not clear exactly when Eliab Capron first got word of the Fox Sisters and their alleged abilities, but it could plausibly have been at the Seneca Falls Convention. Capron supplies some of this backstory in Singular Revelations: Explanation and History of the Mysterious Communion with Spirits (1850), co-authored with Henry D. Barron. Capron excerpts a passage from his personal journal to chronicle his first meeting with the Foxes:

"On the 23d of November, 1848, I went to the city of Rochester on business. I had previously made up my mind to investigate this so called mystery, if I should have an opportunity. In doing so, I had no doubt but what I possessed shrewdness enough to detect the trick, as I strongly suspected it to be, or discover the noise if it should be unknown to the inmates of the house" (58).

Writing decades later, eldest sister Leah Fox Underhill acknowledges that Capron was initially introduced as a skeptic, keen on debunking the sisters, but was soon won over as a true believer and advocate (54).

As Capron was building a rapport with the Fox family, he was also developing credentials in the study of phrenology, the pseudo-science of understanding the dimensions and features of the skull as a predictor of intelligence (often according to racist, classist, and gendered presumptions). In a letter from Eliab dated September 22, 1849, reprinted in The American Phrenological Journal, the Caprons are present and active in the founding meeting of the Auburn Phrenological Society. A synopsis of the gathering outlines the society’s goals, including the establishment of “a Library, a Phrenological Cabinet, and Reading Room” and “the collection of Skulls of Men and Animals” (352). A growing awareness of phrenology represents its own sea change for Capron, apart from the other sea change he was then participating in with the Fox Sisters: “Hundreds who have heretofore paid no attention to Phrenology, now learn and advocate it with a zeal worthy of the cause.” Eliab has been elected as Corresponding Secretary, Rebecca as Recording Secretary, and Henry D. Barron (Eliab’s Singular Revelations co-author) will act as treasurer. The letter expects that the society “will probably meet every week during the winter.” Rather than asking how the Caprons’ simultaneous engagement with spiritualism, suffrage, abolition, and phrenology are mutually negating, it is important to ask how they might have been construed as mutually informative and were made to fit into coherently into a single worldview. Perhaps Eliab was tentatively in search of some cranial feature or metric that could be used to establish an individual’s abilities as a spirit medium.

As 1849 wore on, the spirits that so bothered the Fox sisters began pressuring them for publicity. Threatening to harass the sisters endlessly with their knocks, the unruly ghosts gave instructions for the organization of a public exhibition in Rochester. Per their directives, the séance would involve Leah and Maggie. Cathie was ordered not to attend the event and ultimately stayed in the Caprons’ home in Auburn. This was meant to serve as a short sabbatical from all the attention she had been receiving, from humans and former humans alike (Underhill 100). The spirits requested that Corinthian Hall in Rochester be secured for the demonstration (tapping, “Hire Corinthian Hall”). They also made it clear that Eliab was to address the audience assembled (Underhill 62-3). Leah Underhill remembers Capron as being wary of the ridicule that would be heaped upon the Fox family and himself for taking the matter to the public, but the spirits reassured him otherwise.

The séance and address took place on November 14, 1849. Regarding Capron’s speech, Leah underscores his agnosticism and his focus on the empirical. “Mr. Capron, in delivering the lecture, depended more upon his knowledge of the facts, as they had then occurred, than on any theory of his own, or of others, in regard to the rappings” (63). Following the exhibition, the sisters were subjected to a battery of tests over “three days of efforts to solve the mystery” by members of Rochester's doubting public (Peck 510). These tests partially consisted of a reproduction of the spirit raps at a new location, the Rochester meeting hall of the Sons of Temperance; a strip-search of the sisters conducted by local women; and a test of the rappings conducted while the sisters stood on a glass surface, to eliminate the possibility that some electrical device or current was being manipulated to produce the noises (Peck 515-6).

In contrast to the air of sober disquisition with which Capron approached his Rochester address, he would remain a spitfire in print when dealing with the Foxes’ detractors. In the December 21, 1849 edition of The North Star, Capron lambastes an anonymous critic, “J.D.,” for his “barefaced misrepresentations.” This involved rebuffing J.D.’s parody of Capron’s own millennial rhetoric. “As to the ‘not very satisfactory origin for what is claimed to be the opening up of a new world ー the discovery of a new science,’ I have only to say that the Jews were at one time as illy satisfied with the ‘origin’ of what was really ‘claimed’ to be the opening up of a new world ー the discovery of a new science." Capron decries this bit of public criticism as being purposefully oblivious to evidence of a broader spiritual awakening, in “Rochester, in the towns adjoining, in Hydesville, in Auburn, in Sennett." Capron concludes with some ad hominem venom: “I can conceive of no one who is better prepared to judge of the spirit of an ‘old Bachelor’ than ‘J. D.,’ having, for some years occupied that ‘whimsical fidgetty’ position himself.”

After the evident success of Rochester, Capron began urging the Fox family to allow him to take the sisters on a chaperoned tour of New York City. This trip would, it appears, be a junket that would introduce the Foxes to a broader audience, which included the city’s intellectual and cultural elites. The visit took place on June 18, 1850 (Gorman 7). While there, Capron helped to arrange interviews between the sisters and notables like Horace Greeley; George Ripley (two dyed-in-the-wool Fourierists); James Fenimore Cooper; and William Cullen Bryant, among others (Underhill 128, 137).

For a young newspaper man like Capron, the sisters’ special abilities had all the makings of a story of the century. Capitalizing on his access to the Foxes and preternatural experiences, Capron self-published Singular Revelations in 1850, and the book merited at least two editions. Attempting to strike a tone of dispassionate objectivity, the text respects the legitimacy of outside skepticism and, in turn, earnestly tries to incorporate a slew of primary sources, eyewitness accounts, and descriptions of personal paranormal experiences. The names of those who have witnessed something gives a revealing snapshot of Capron’s social network at that moment in history.

And the manifestations described by Capron have far surpassed the simple occurrence of disembodied knocking:

"On one occasion when several persons were present, the guitar was taken from the hands of those who held it, (they taking hold of hands,) and put in tune and commenced playing while it passed around the room above their heads. It was also taken from one person and passed to others in the room. In this way for nearly two hours it continued to play and keep time with the singing; and the guitar taken by this unseen power to different parts of the room while playing. The witnesses present at this time, were James H. Bostwick, Esq., Police Justice, Miss Sarah Bostwick, Mrs. F. Smith, H. D. Barron, and R. M. C. Capron" (72).

Among the list of first-person observers given, Eliab names his own spouse as a witness to this paranormal happening, which sounds extreme to the point of ridiculousness. Elsewhere, Capron invokes Frederick Douglass and Elias J. Doty (Signer #78) as paranormal eyewitnesses, without necessarily detailing what exactly it was that they experienced (96, 74).

Singular Revelations would be followed up with the sprawling 438-page Modern Spiritualism: Its Facts and Fanaticisms, It Consistencies and Contradictions, published in Boston and New York in 1855. With chapter headings that include “Manifestations in New York City,” “Manifestations in Boston,” “Manifestations in Philadelphia,” "Manifestations in Washington, D.C.," Capron extrapolates the otherworldly happenings of the Burned-Over District more broadly to the Northeast (vii-ix). To inject an aura of Protestant respectability and precedent into the recent occurrences, Capron documents the spirit rappings, experienced in 1716 by John Wesley, in both texts (24-30, 30-8).

In all belief, there is at least the hint of some immediate personal utility. Séance would have allowed Capron and his cohort to make direct, unmediated contact with the afterlife. This could be done without any interlocutory, interpretive role played by the clergy and “Priestcraft” he so detested, preaching restraint. The spirits could authoritatively disagree with secular powers-that-be, especially in regards to what ought to be done about the lives of disenfranchised women and the enslaved. Mediumhood also indirectly undermined the sectarianism that Capron so often deplored in his writing. Not coincidently, “the numerous isms and ites of the religious or anti-religious world,” as Capron deems it, had hitherto proven a persistent obstacle in the campaign to end slavery (Singular 6). Spiritualism would have also allowed Capron to engage in a form of millennialism that anticipated sweeping reform on planet earth as not only being likely, but imminent--as the posthumous message above from Ben Franklin insists. Capron asks if the recent events are ephemeral or “whether it be the commencement of a new era of spiritual influx into the world; it is something worthy of the attention of men of candor and philosophy” (Singular 48). Clearly, Capron has a wish list of all the ills that would be eradicated in the brave new spiritual world he imagines.

If Capron was a knowing accomplice or charlatan and engaged the Foxes and spiritualism with venal, ulterior motives, he nevertheless managed to fool Susan B. Anthony. She writes about Capron in a journal entry composed after an 1854 dinner in Philadelphia with Eliab, Rebecca, Sarah Grimke, Lucretia Mott (Signer #1), and James Mott (Signer #81). “Eliab Capron doesn’t believe, he knows there is a reality in spirits disembodied, communicating with the living” (underlining Anthony's, quoted in Gordon 254). Capron seemed to believe that the increasing spirit voices being channeled through human media were harbingers of bigger changes to come. He thought that humanity should engage these voices in earnest, and he helped to spur scores of other Americans into believing the same, for the next two centuries.

Instead of remaining in Auburn to continue working with the Foxes and writing on those experiences, Eliab and Rebecca relocated in 1850 to Providence, Rhode Island, where he had been hired as editor of The Providence Mirror (Underhill 195). Lacking permanent accommodations, Eliab is recorded twice in the 1850 census. During a headcount taken on August 7, Eliab’s profession is listed as “Editor,” and he is included in the household of Orin and Jerusha Capron, members of his extended family (Holden 71). By September 9, Eliab and Rebecca turn up in the home (likely a boarding house) of Carmeline and Hunting Rowe. Rowe’s occupation is listed as “Newspaper Vending,” which hints that he might have been a professional contact.

Their move to Rhode Island enabled Rebecca and Eliab to attend the first national suffrage convention, held in nearby Worcester, Massachusetts, in October 1850. Much like its account of Seneca Falls, The History of Woman Suffrage specifies that Eliab, in a limited list that includes Sojourner Truth, “took part” in the proceedings and discussion of the convention (224). Not many individuals attended both the convention at Seneca Falls and the one at Worcester (with the different conventions later providing competing points-of-origin for the rival camps of the AWSA and NWSA). This small group of dual attendees may very well be limited to Capron, Douglass, and Lucretia Mott.

In August 1858, the Caprons would transition again, this time to the Philadelphia area. This time, Eliab had secured the editorship of The Chester County Times, of West Chester (Futhey and Cope 332). A handwritten letter from Eliab, dated November 28, 1860, composed on Chester County Times letterhead, is addressed to William Lloyd Garrison and asks after a resource regarding the dubious constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act. During this period, Eliab also began moonlighting in state-level government. Articles published in The Mariettian and The Pittsburgh Post recognize Capron as the Assistant Clerk to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives; the Post article even charges Capron with being involved in a wartime secret society of Pennsylvania’s Union loyalists (“Senator Cowan,” “Secret League”).

Eliab was not the only one attempting to settle into a career at this point. “Rebecca M.C. Capron” is included in a directory of matriculants enrolled in Philadelphia’s Female Medical College of Pennsylvania (founded in 1850) for academic years 1853-4 and 1854-5 (14). Later the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, FMCP was the “first school anywhere established to train women in medicine and offer them the M.D.” (Peitzman 1). During this same period, James Mott served as one of the college’s trustees and donors, likely providing an important contact for Rebecca (i, 20). It is not clear if Rebecca completed the degree. One likely influencing factor was the birth of a daughter, Evalyn, in October 1856. By the 1860 census, the Caprons are living in West Chester. The household includes Evalyn, now 4; Mary B. Woodward, Eliab’s mother, 59; and a seventeen-year-old named Sarah Smith, an African-American from Pennsylvania, working as a “Domestic.”

Rebecca’s training in the medical field might shed some light on her death on February 16, 1864, at age 39, after succumbing to pneumonia (Wellman et al., 336). If she used her FMCP background to care for the sick in some unofficial capacity, it would have exposed her to diseases at a time when Germ Theory was anything but settled science. Identified on her tombstone as “Wife of E.W. Capron,” Rebecca lies buried in Wildwood Cemetery in Williamsport, Lycoming County, Pennsylvania, located in the north-central part of the commonwealth (“Rebecca Capron”).

Following Rebecca’s death, Eliab and Evalyn also surface in Williamsport. In 1868, Capron is congratulated by a friendly newspaper editorial for founding The Daily Bulletin in Williamsport, “A live and spicy Republican paper” (“We Welcome”). In the 1869-70 Boyd’s Williamsport City Directory, he is listed as a “common council” member in city government (26). The 1870 census also places the Caprons in Williamsport. Eliab is an “Editor of Paper” with an assessed estate of $11,000. He has married Agnes Cooper, (born September 23, 1830, in Pennsylvania), whose own assets are valued at $3,500. It should be noted that Rebecca and Agnes shared the same surname, and it remains to be seen if they were in some way related.

Eliab is present at the Philadelphia annual meeting of the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association in November 1870, serving as a member of the gathering’s executive committee. The resolution passed at the meeting urges that “we respectfully request of the editors of the newspapers of this city and of the State manly co-operation in our work, and such aid and service as they would desire of the controllers of the newspaper press if they were struggling for their own political enfranchisement” (“Woman Suffrage”). It is conceivable that Eliab contributed some language to this portion of the resolution, given his profession and his fondness elsewhere for italicization.

In space taken out in the 1873-4 Boyd’s Pennsylvania Business Directory, Eliab advertises his printing and editorial services in Williamsport, along with a new publication, “The Weekly Epitomist.”

That same year, Eliab began to move around Pennsylvania and New York State at an exhausting pace, transitioning frenetically between towns and professional projects. Whether this was a vocational necessity for an itinerant editor or a matter of personal preference is unknown. In 1872, he purchased, with a partner, the Republican-oriented The Herald and Democrat, based out of Oneonta, New York, and retired from the paper in January 1875 (Hurd 34). In February 1877, Capron partnered to work on the Republican in Fulton County, New York. This would last until January 9, 1879, “when impaired health occasioned the retirement of Mr. Capron” (Frothingham 413).

In September 1878, Evalyn married Walter Youle Harvey of Wilmington, Delaware, in a Catholic ceremony in Philadelphia (“Evalyn May Capron”). According to the information incorporated on his headstone, Walter passed away after only three years of marriage, on February 5, 1881, at age 29 (“Walter Harvey”). Evalyn would remain in Philadelphia and become an educator of deaf-and-hard-of-hearing children. In the 1880s, “Evalyn M.C. Harvey” is listed as a teacher in the 1882 and 1898 annual reports of Philadelphia’s Home for the Training in Speech of Deaf Children Before They are of School Age and as a founding member of a society to facilitate deaf education (30, 11).

Like her father exactly 50 years before, Evalyn is recorded twice in the 1900 census. Living with the family of Ruby and Walter Bryant, “Evalyn M Harvey” is recorded as a “Boarder” in Saratoga, New York, and as “Evalyn M. Capron,” “Governess” in Philadelphia—her birthdate, family’s states-of-origin, and widowed status being identical in both records. This most likely represents a well-heeled family’s trip to a summer home during the early months of the summer. A 1902 Philadelphia directory includes Evalyn, with the occupation of “linguist” (1050). By the 1930 census, Evalyn lives in Manhattan, and she would pass away in Manhattan in September 1943, aged 86.

In the 1880 federal census, Eliab, now 60, pops up in Haddon, Camden County, New Jersey. His profession is listed as “Retired Editor”; Agnes’ profession is listed as “Keeping House.” Evidence suggests that Eliab and Agnes parted ways under curious circumstances in the 1880s, perhaps via a separation or informal divorce. In the 1885 New Jersey state census, Agnes is now domiciled with one “Joseph L. Chapman.” In the 1895 state census, Agnes is again listed immediately next to Chapman, suggesting that their domestic arrangement was not a temporary one. Still using her married name, “Agnes Cooper Capron” passed away in Philadelphia on June 30, 1906, a resident of Haddon, succumbing to heart issues. In the 1889 directory for New York City, an Eliab W. Capron is listed as living on East 27th Street (285). Eliab died in Manhattan on April 18, 1892, and he is buried in an unmarked grave on the family plot of his son-in-law, Walter Harvey, at the Chester Rural Cemetery in Chester, Delaware County, Pennsylvania (“Eliah Capron”).

In a lifetime of what seems to have been endless movement, Eliab Capron was uncompromisingly committed to spiritualism, abolition, suffrage—his place at the nexus of each cause reveals how truly intertwined and co-dependent the ideologies of the Burned-Over District were.

Works Cited

“Agnes Capron.” New Jersey State Census, 1885. Haddon, New Jersey.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Agnes Capron.” New Jersey State Census, 1895. Haddon, New Jersey.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Agnes Cooper Capron.” Record of a Death in Philadelphia. 30 June 1906.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Constitution of the Auburn Phrenological Society.” The American Phrenological

Journal and Miscellany. A. Waldie, 1849, p. 352.

Bowman, Fred Q. 10,000 Vital Records of Western New York, 1809-1850. Baltimore,

MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1985.

Boyd’s Williamsport City Directory 1869-70. Williamsport: Boyd’s, 1869.

Boyd´s Business Directory of Over One Hundred Cities and Towns in Pennsylvania.

Boyd’s, 1873-74.

Capron, E.W. “To Farmington Monthly Meeting of Friends.” The Liberator (Boston,

MA), 15 Mar. 1844, p. 2.

---. “The Mysterious Rapping—Public Meetings for Investigation.” The North Star

(Rochester, NY), 21 Dec. 1849.

---. Modern Spiritualism: Its Facts and Fanaticisms, Its Consistencies and

Contradictions. Bela Marsh, 1855.

---. “My Dear Sir.” https://archive.org/details/lettertomydearsir00andr. Accessed June

4, 2019.

Capron, E.W. & H.D. Barron. Singular Revelations. Auburn, 1850.

“Capron Family.” Federal Census, 1850. Providence, Rhode Island.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Capron Family.” Federal Census, 1860. West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Capron Family.” Federal Census, 1870. Williamsport, Pennsylvania.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Capron Family.” Federal Census, 1880. Haddon, New Jersey. Ancestry.com. Accessed

June 4, 2019.

“Eliah Capron.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/

197190151/eliah-w_-capron. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Evalyn May Capron.” Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town Records, 1669-

2013. Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Evalyn M. Capron.” Federal Census, 1900. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Evalyn M. Harvey.” Federal Census, 1900. Saratoga, New York.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Evalyn M. Harvey.” Federal Census, 1930. New York, New York.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

"Evalyn M. Harvey." New York Extracted Death Index, 1862-1948.

Female Medical College of Pennsylvania. Annual Announcement and Catalogue of

Students. Jas. B. Rodgers, 1850.

Frothingham, Washington. History of Fulton County.D. Mason, 1892.

Futhey, J. Smith, and Gilbert Cope. History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with

Genealogical and Biographical Sketches. L. H. Everts, 1881.

Gopsill’s 1902 Philadelphia City Directory. Gopsill, 1902.

Gorman, Daniel. “The Man Behind the Curtain: E.W. Capron and the Early Days of Spiritualism.”

Post Family Papers Project, https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/exhibits/show/post-family- papers/post-project. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Gordon, Anne Dexter. The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B.

Anthony. Rutgers University Press, 1997.

Holden, Frederic Augustus. Genealogy of the Descendants of Banfield Capron, from

A.D. 1660 to A.D. 1859. G.C. Rand & Avery, 1859.

Hurd, Duane Hamilton. History of Otsego County, New York. Everts & Fariss, 1878.

National American Woman Suffrage Association. NAWSA Handbook. 1893.

National Spiritualist Association of Churches.“Hydesville Park History”

https://nsac.org/who-we-are/fox-property-history/. Accessed 3 June 2019.

“A New Secret League.” The Pittsburgh Post (Pittsburgh, PA), 17 Apr. 1862, p. 1.

New York City Directory, 1889.

“Our Roll of Honor. Listing Women and Men Who Signed the Declaration of Sentiments

at First Woman’s Rights Convention, July 19-20, 1848.” Library of Congress, Washington.

Peck, William Farley. Semi-Centennial History of the City of Rochester: With

Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. D. Mason & Company, 1884.

Pennyslvania Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. Annual Report. E.G. Dorsey, 1882.

Philadelphia Home for the Training in Speech of Deaf Children Before They are of

School Age. Annual Report. 1898.

Philadelphia City Directory, 1902.

Peitzman, Steven Jay. A New and Untried Course: Woman’s Medical College and

Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850-1998. Rutgers University Press, 2000.

“Rebecca Capron.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/

144875755/rebecca-m-capron# Accessed June 4, 2019.

Report of the Women's Right Convention. Rochester: John Dick, 1848.

“Rowe Family.” Federal Census, 1850. Providence, Rhode Island.

Ancestry.com. Accessed June 4, 2019.

“Senator Cowan.” The Marriettian (Marrietta, PA), 29 Mar. 1862, p. 2.

“Signers of Declaration of Sentiments at Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.” Seneca

County Courier-Journal (Seneca Falls, N.Y.) 19 July 1923, p. 1.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, et al. History of Woman Suffrage. Ayer Company, 1881.

Underhill, Ann Leah. The Missing Link in Modern Spiritualism. T. R. Knox & Company,

1885.

“Walter Harvey.” Findagrave.com. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial

/197209674/walter-youle-harvey. Accessed June 4, 2019.

Wellman, Judith, Marjory Allen Perez, and Charles Lenhart. Uncovering the

Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Wayne

County, New York, 1820-1880. Wayne County Historian’s Office, 2009.

“We Welcome.” Father Abraham (Lancaster, PA), 14 Aug. 1868, p. 2.

“Woman Suffrage.” The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia, PA), 11 Nov. 1870, p. 3.